You've heard of the Coach creed? Well, what follows is our general COACH SCREED. (We were going to call it 'The Comprehensive Illustrated Guide to Coach Leather'...it does have pictures and is extremely long...but it's just too angry.)

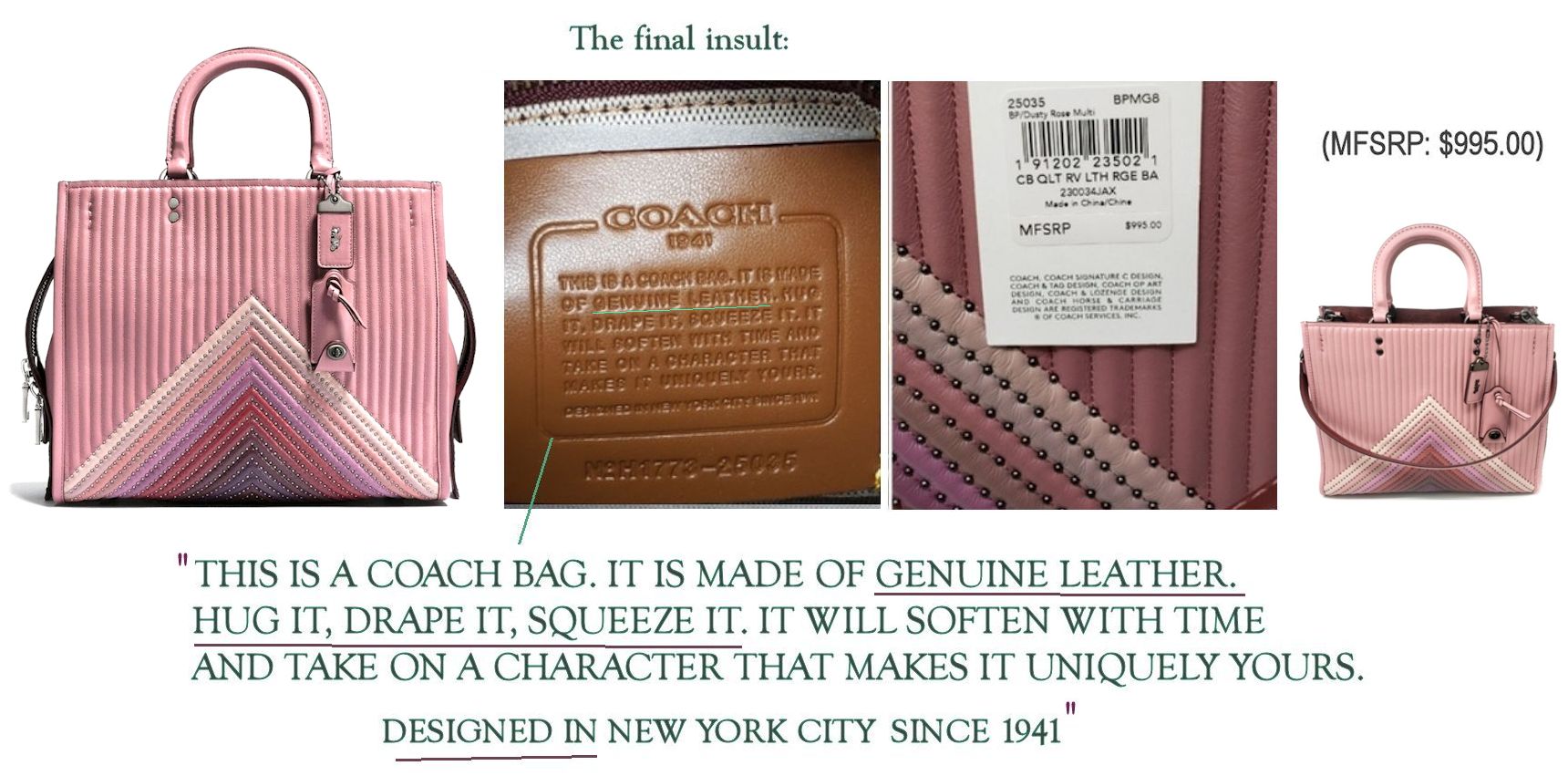

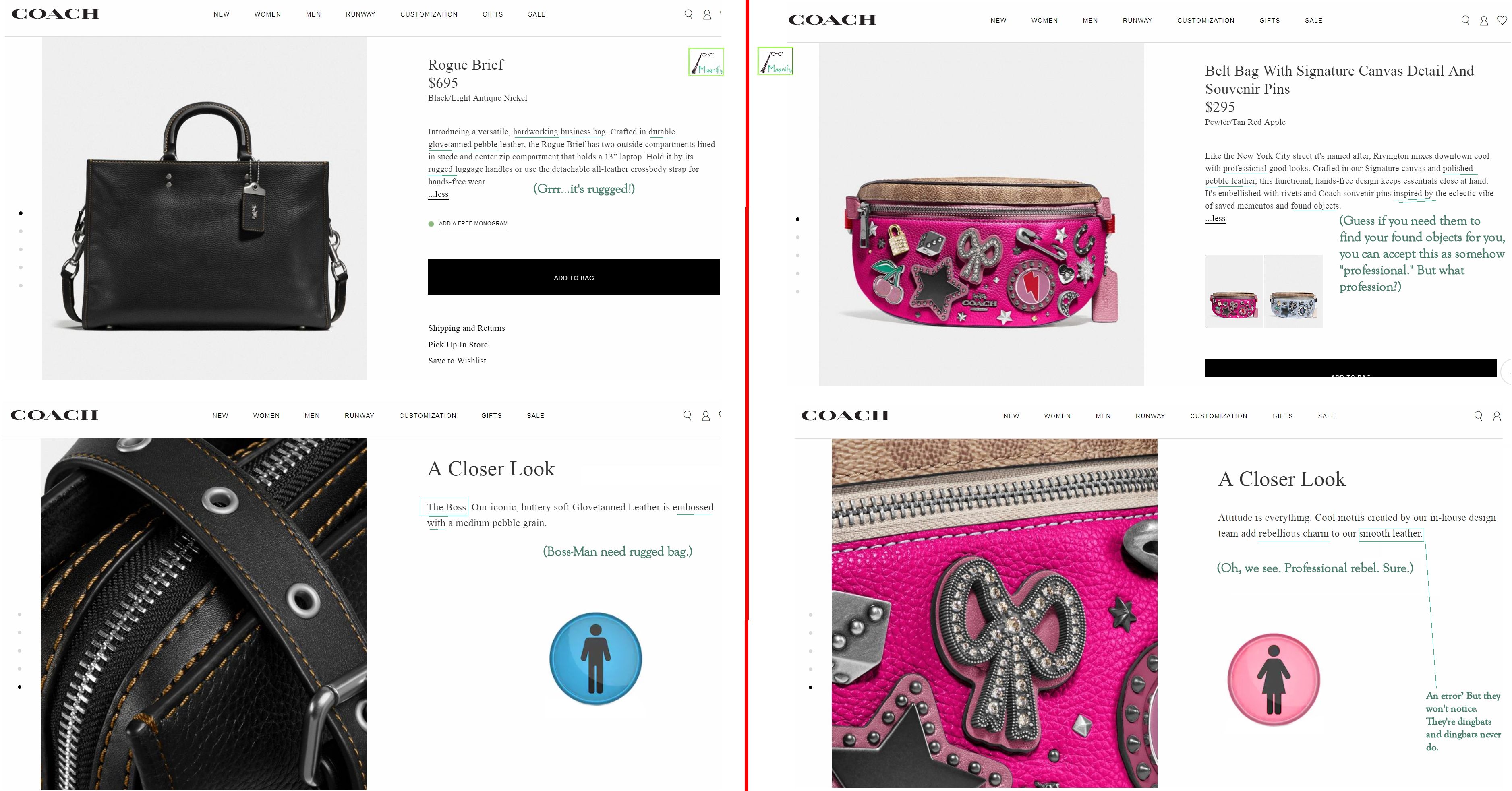

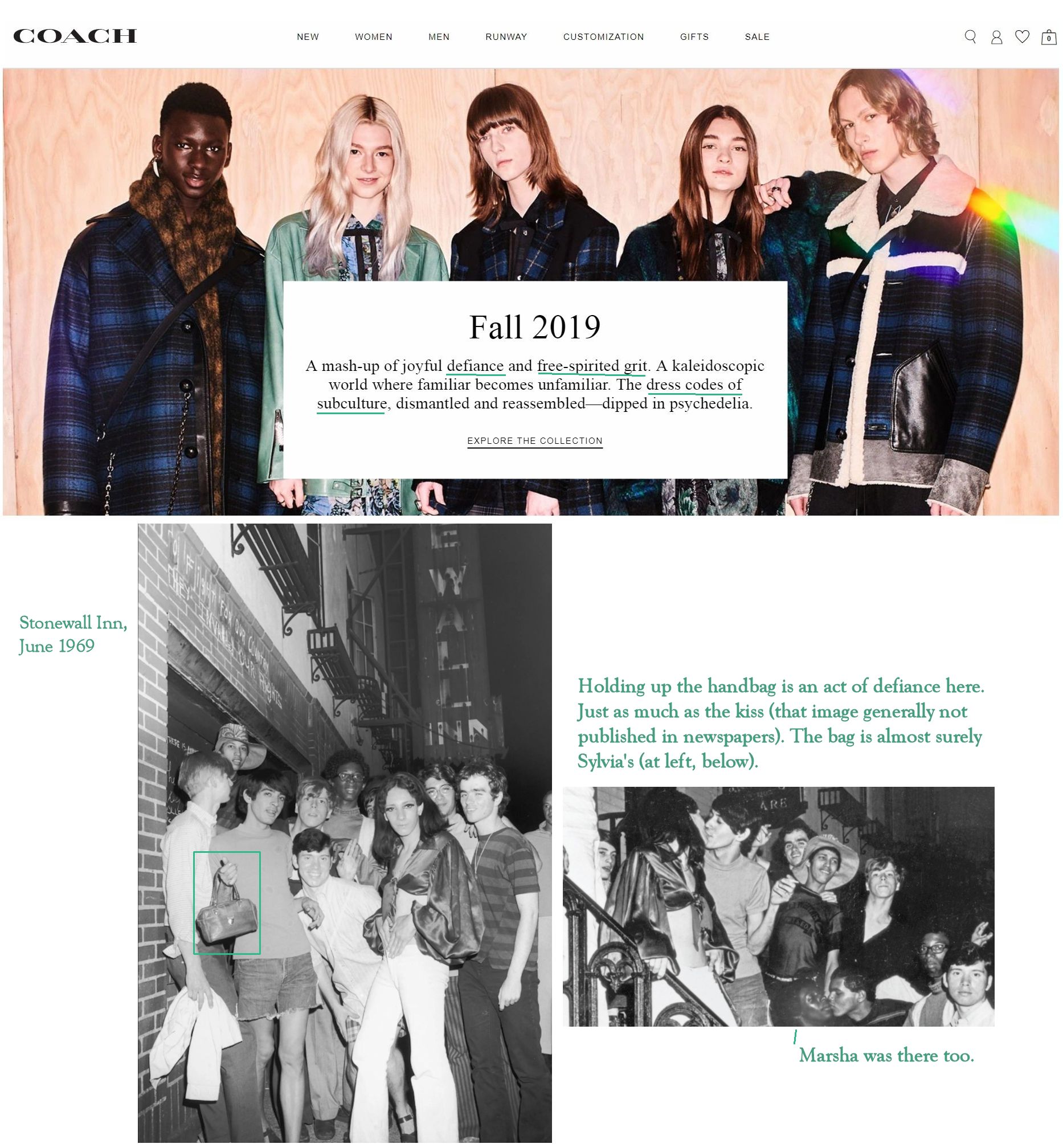

The new Coach/Tapestry, Inc. (name change of conglomerate in 2017, now controls Coach, Stuart Weitzman and Kate Spade) is in the process of repositioning Coach as a 'designer lifestyle brand,' and we're afraid the writing is on the wall here --and in the new wording of the creed itself, which now includes the ominous term "Genuine Leather." The quality of all future Coach bags may hang in the balance. This matters since the essence of what a Coach bag was always came down to one thing: top quality full-grain leather.

If you take away, not just the natural full aniline surface (mostly gone since about 2001), but now even the full-grain leather, what's left to make it a Coach bag at all? What's left to make it any different from any other modern painted, plastic-coated leather handbag? We feel they're gutting out and erasing what had been the very essence of those once-excellent bags. Somebody really has to say something. (And no, the new Tapestry Inc. logo doesn't actually include a black cloud. We just hate them and think it should. Sponsored puff pieces abound, but remember, this is a screed.)

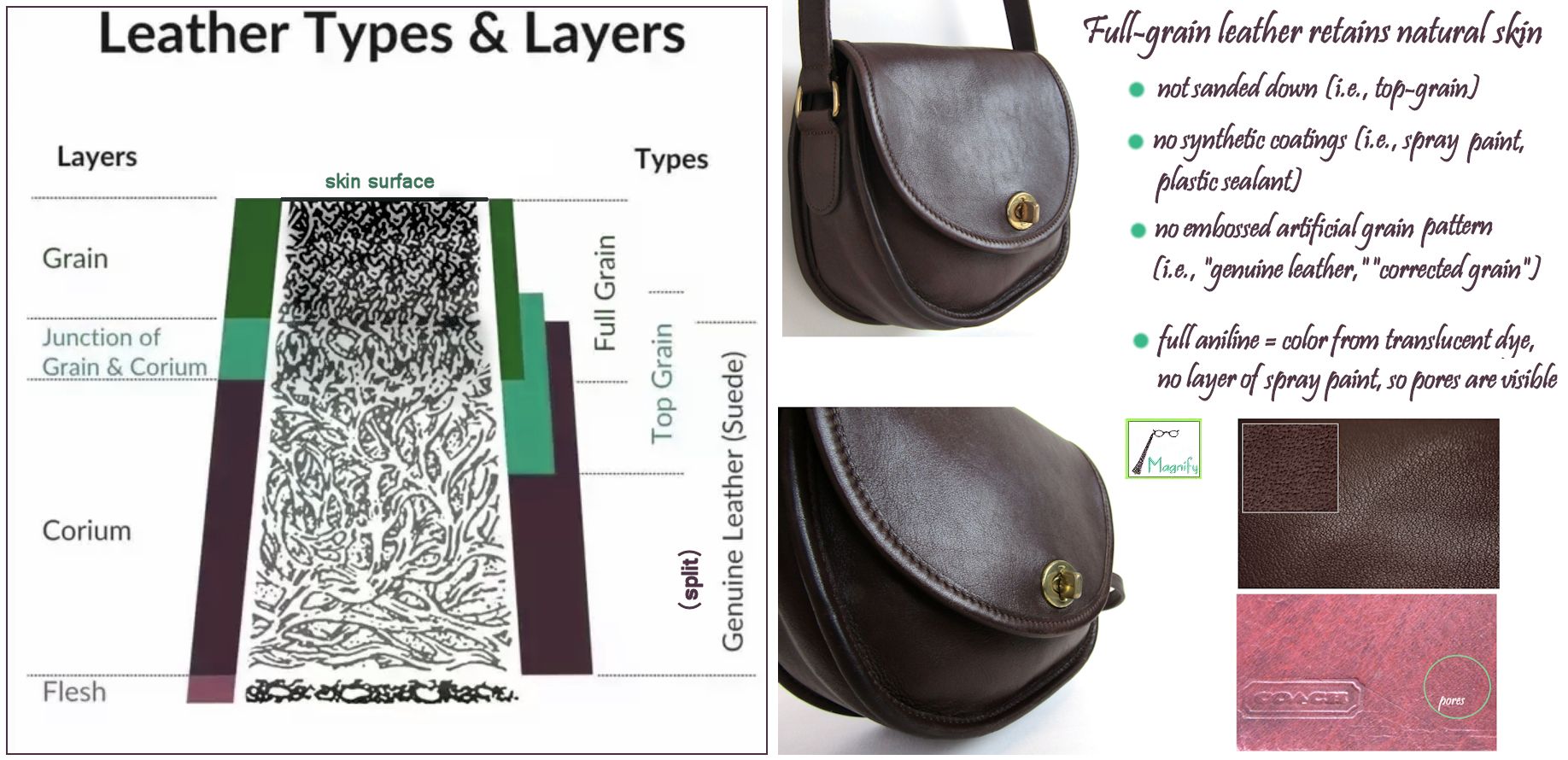

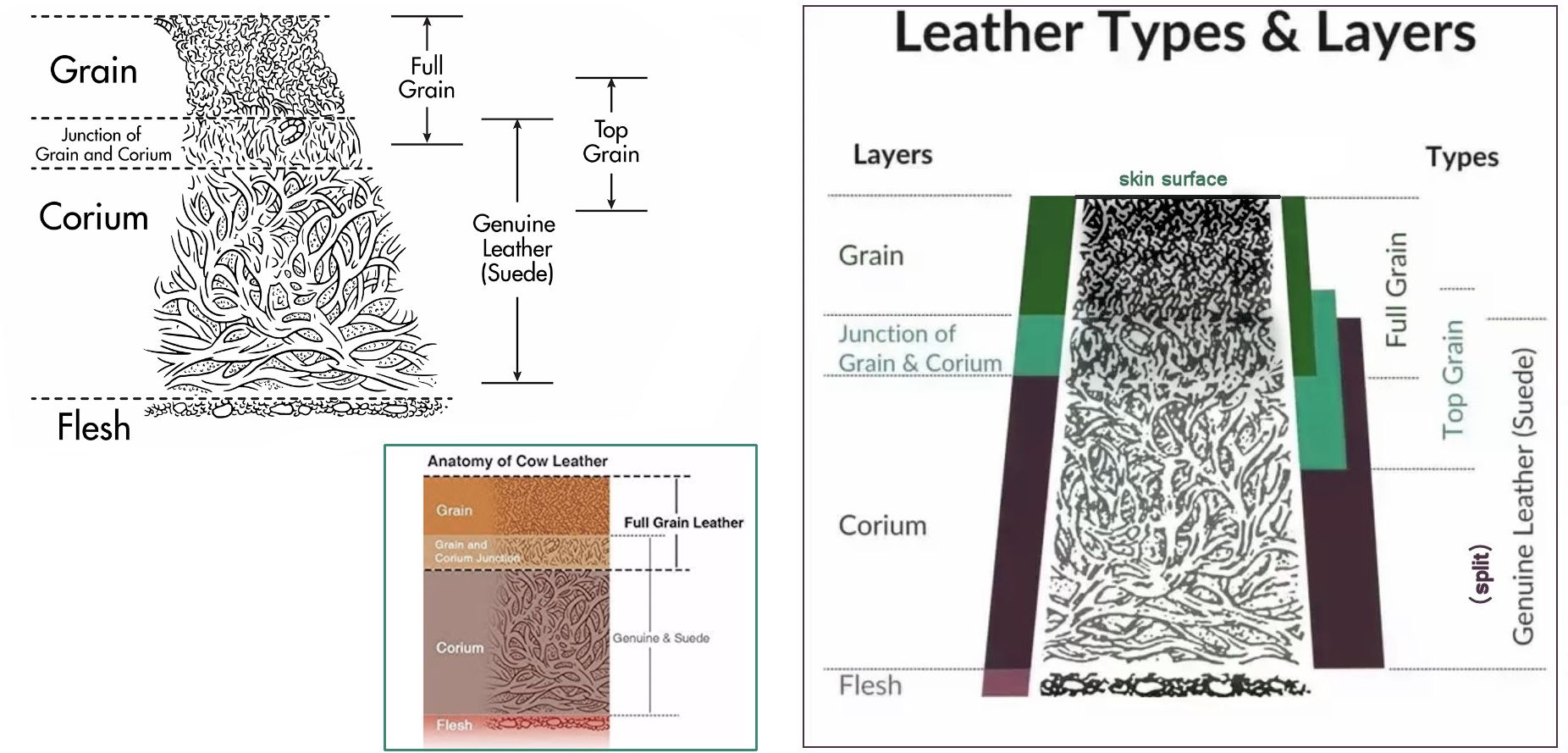

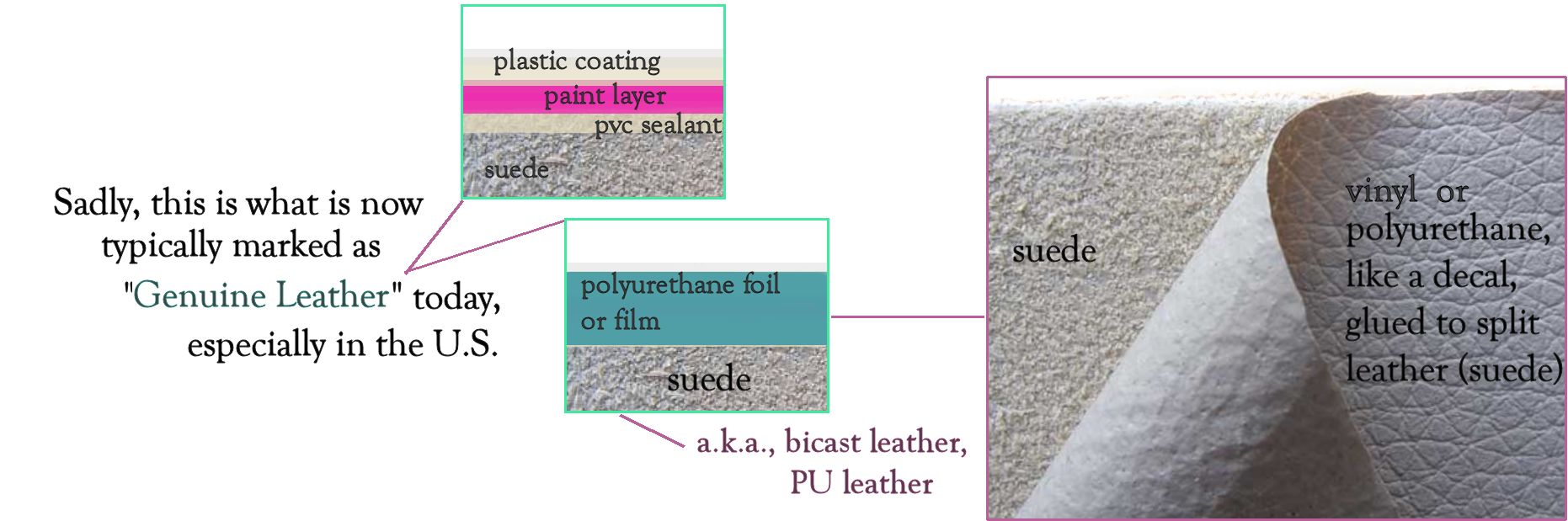

If you already know about the stark quality difference between full-grain full aniline leather and what the modern "genuine leather" wording indicates in the trade, then please tell others right away because many bag-buyers really still don't know, and we think everyone should. If you're unclear, look at the diagrams below or see the quick run-down on what "Genuine Leather" actually is from Business Insider. We're going to get into the details of these industrial processes below, which should make it plain to all that we have every reason to demand more than that from what was once Coach Leatherware.

At an average of $500 for a modern leather Coach bag (and some now priced at three times that), asking for a return to the uncoated, natural surface full-grain full aniline leather of old doesn't seem completely crazy, especially when new-Coach is constantly banging on about their Archive with classic this, legacy that, and everything infinitely and unquestionably "iconic." What was iconic was a sleek functional minimalism, a certain dynamic fluidity of line, always made in uncommonly excellent leather.

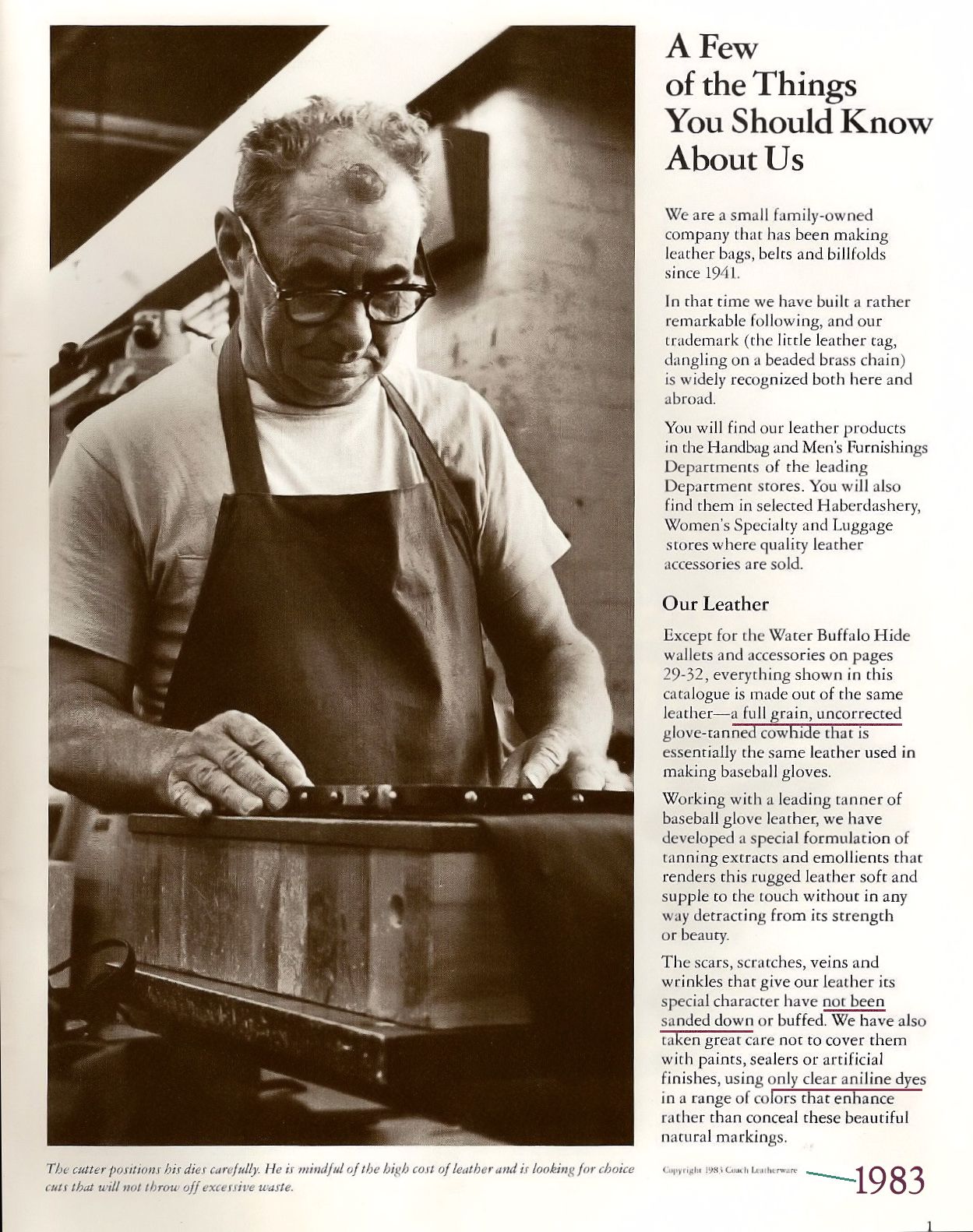

For a run of almost 40 years, c. 1962 - 2000, Coach was making some of the best quality leather handbags available at any price point. And Coach was unique in this, the only large commercial or non-artisanal outfit still making bags with a natural untreated surface, not coated with opaque paints and layers of plastic, as nearly all other leather handbags were, both then and now. A Coach bag was always first and foremost about that leather. Until recently.

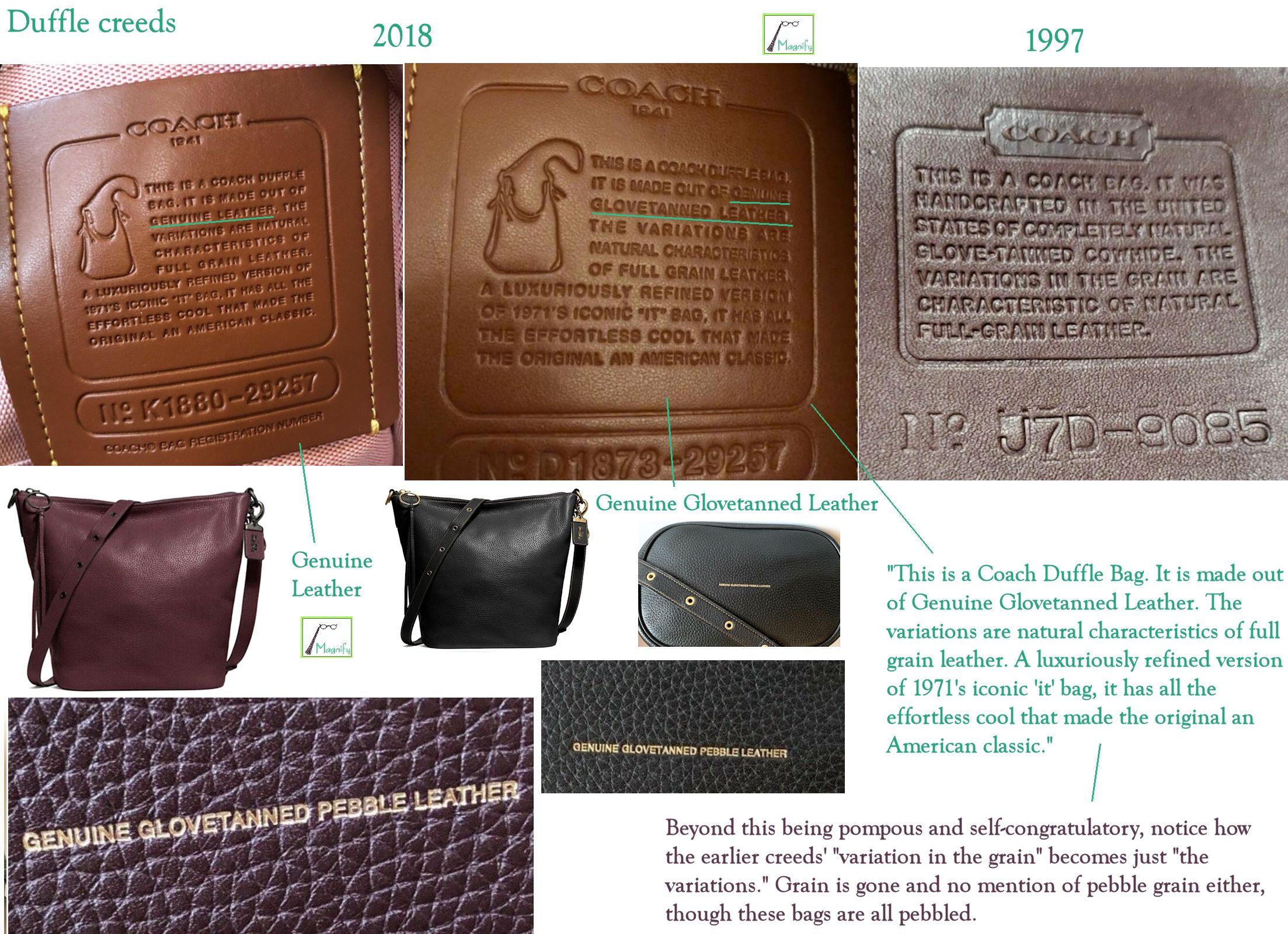

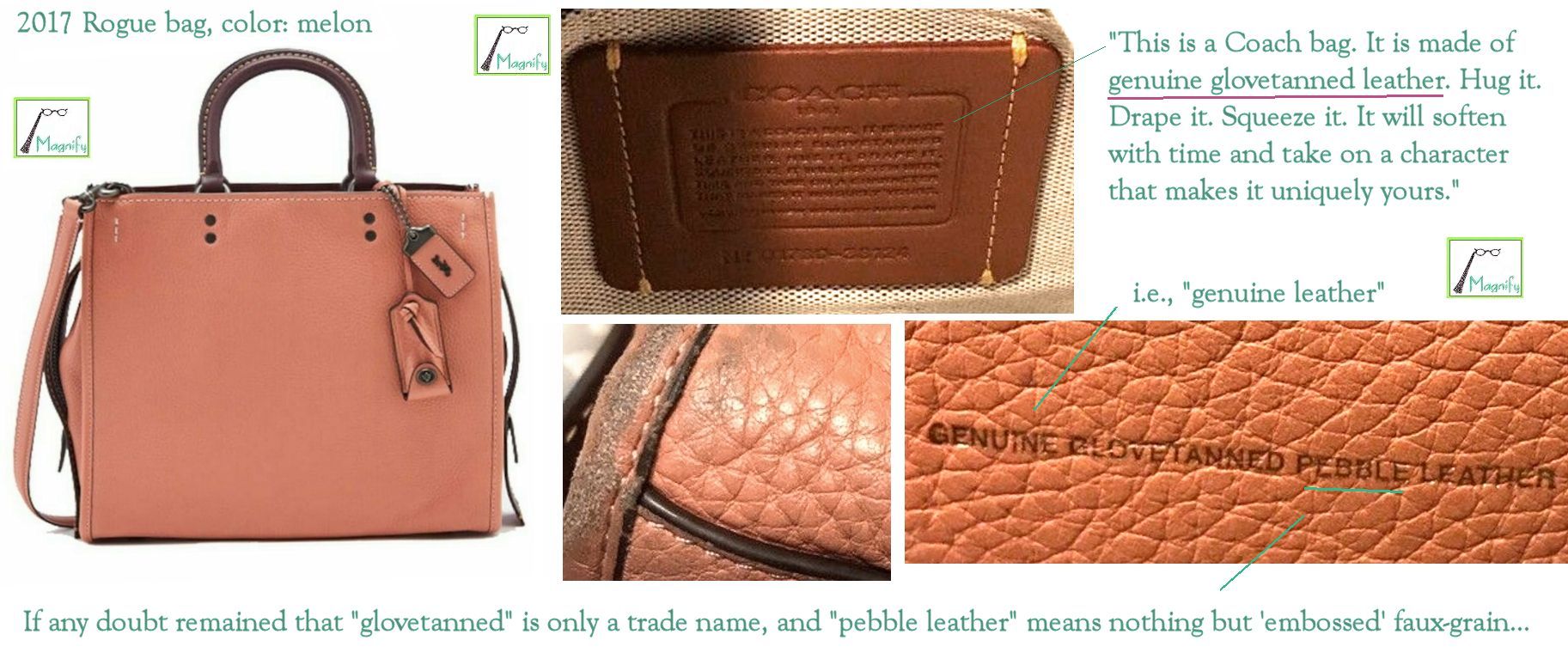

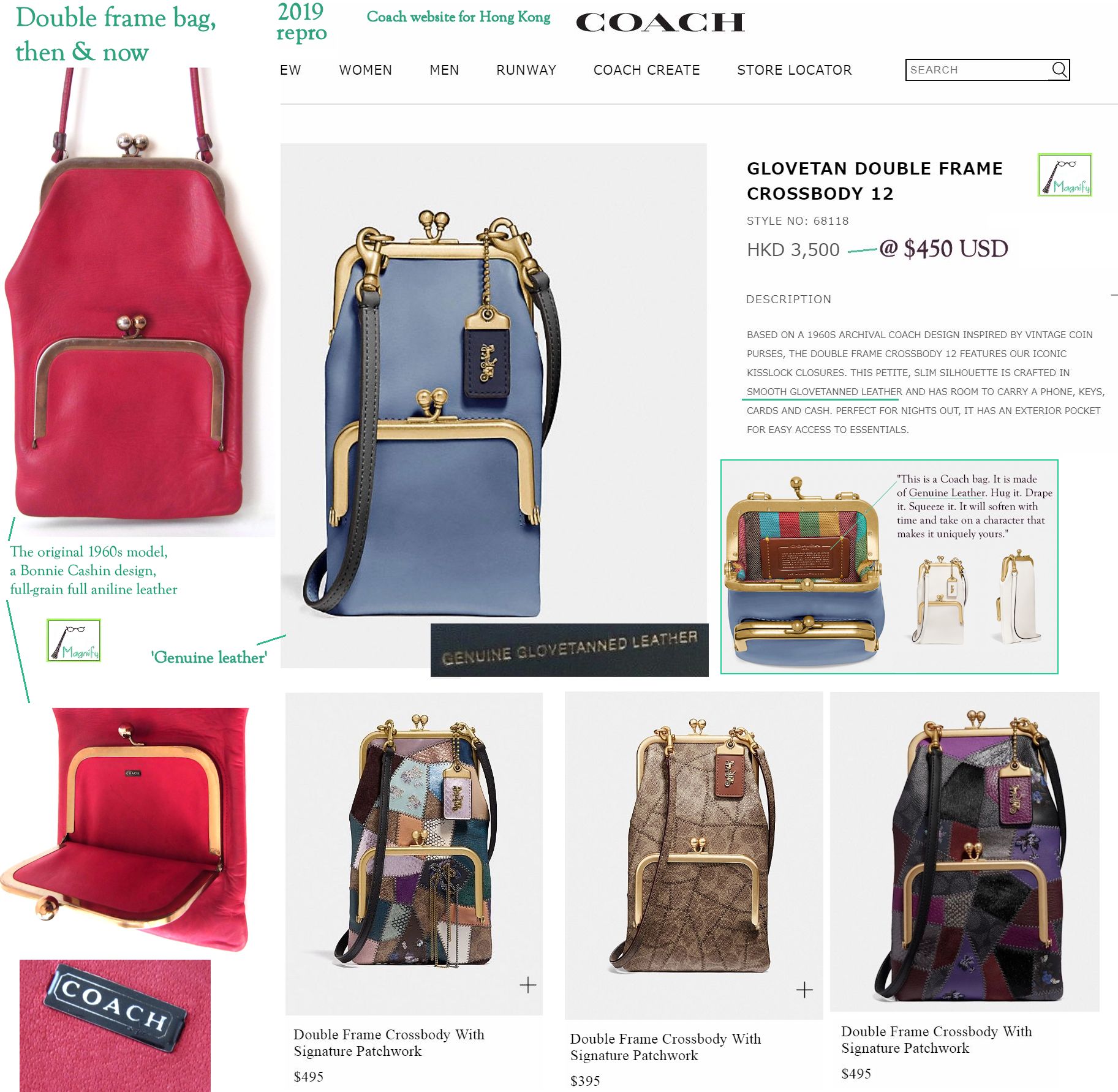

The specific leather used in vintage Coach bags --full-grain hides dyed with translucent aniline dyes-- is the reason the original bags lasted so long, wore so well, looked so good, and actually improved with age. Much as they're touting it lately, the relationship with "glove-tanned" (not even mentioning the truly ridiculous "Genuine Glovetanned Leather" now appearing printed on the bottom of some current bags) was and is nothing but a marketing term. Far from being any legitimate metric of quality in leather (which full-grain actually was), this is just a blinged up way of saying "genuine leather," which we can see reflected in the creed wording in those bags. ("Glove" is just a generic name tanneries use, meaning the tannage for baseball mitts. We'll get into the details of this shortly.) What mattered was the natural surface, which you can only get with full-grain hides through-dyed with aniline colors. And that has been eliminated completely.

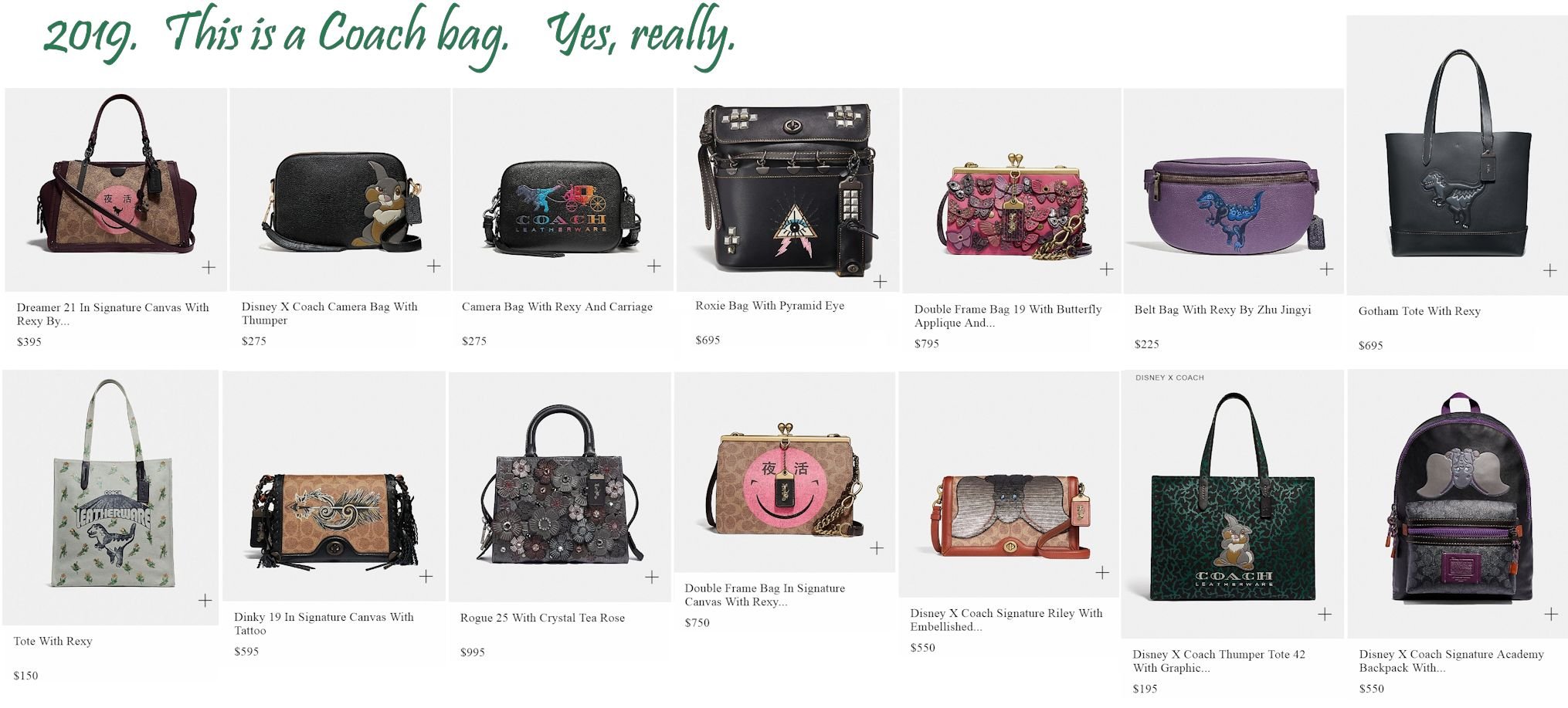

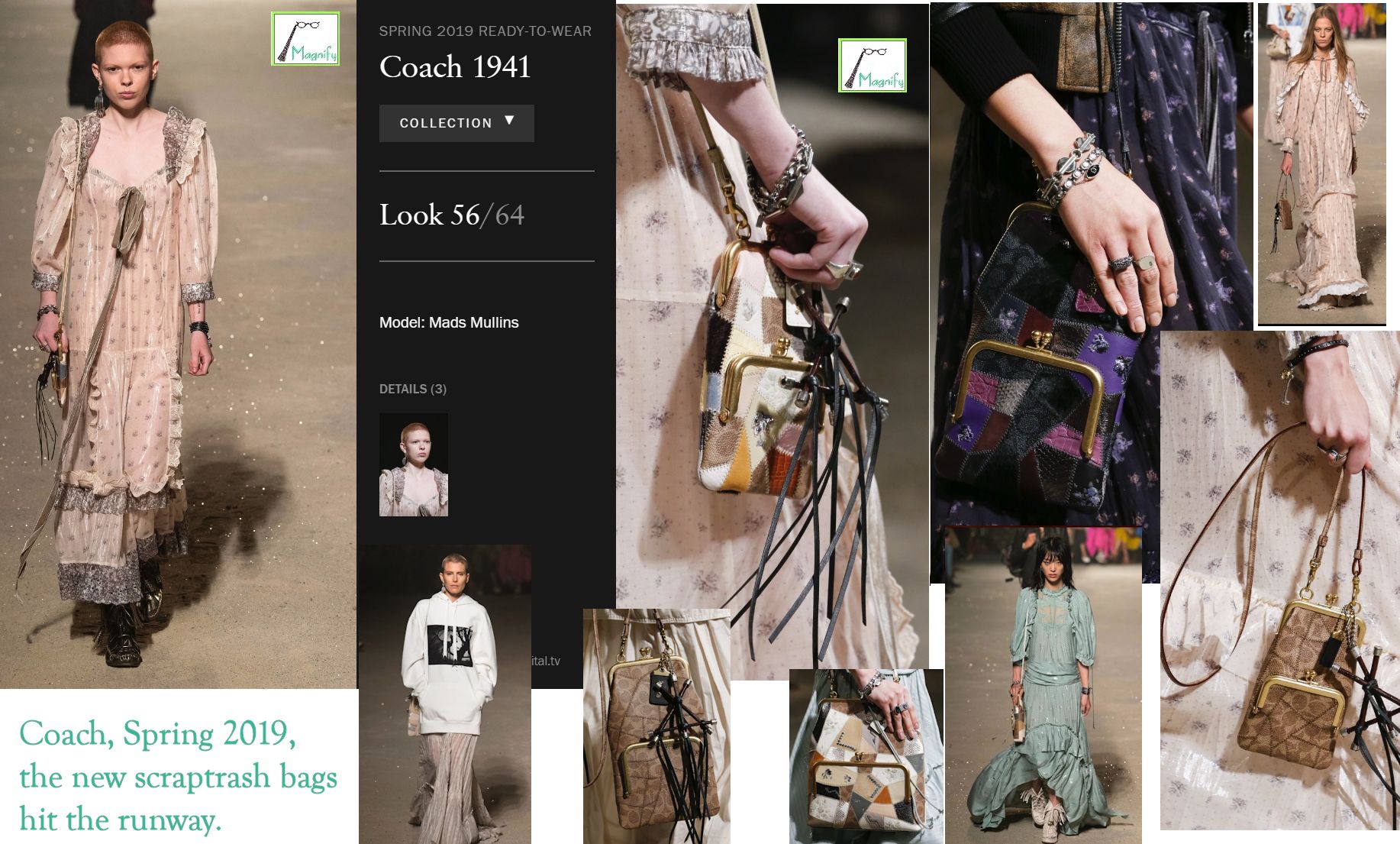

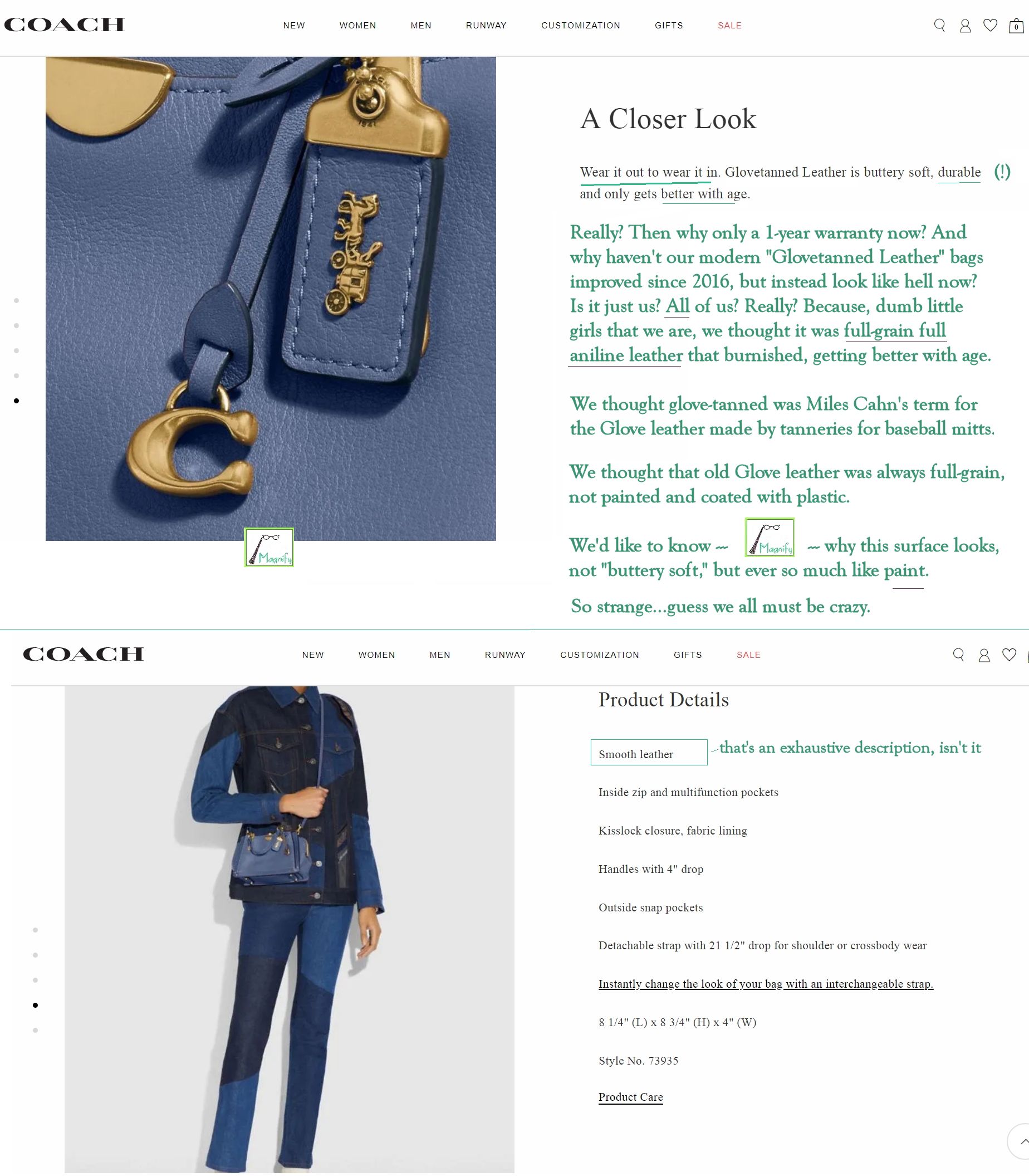

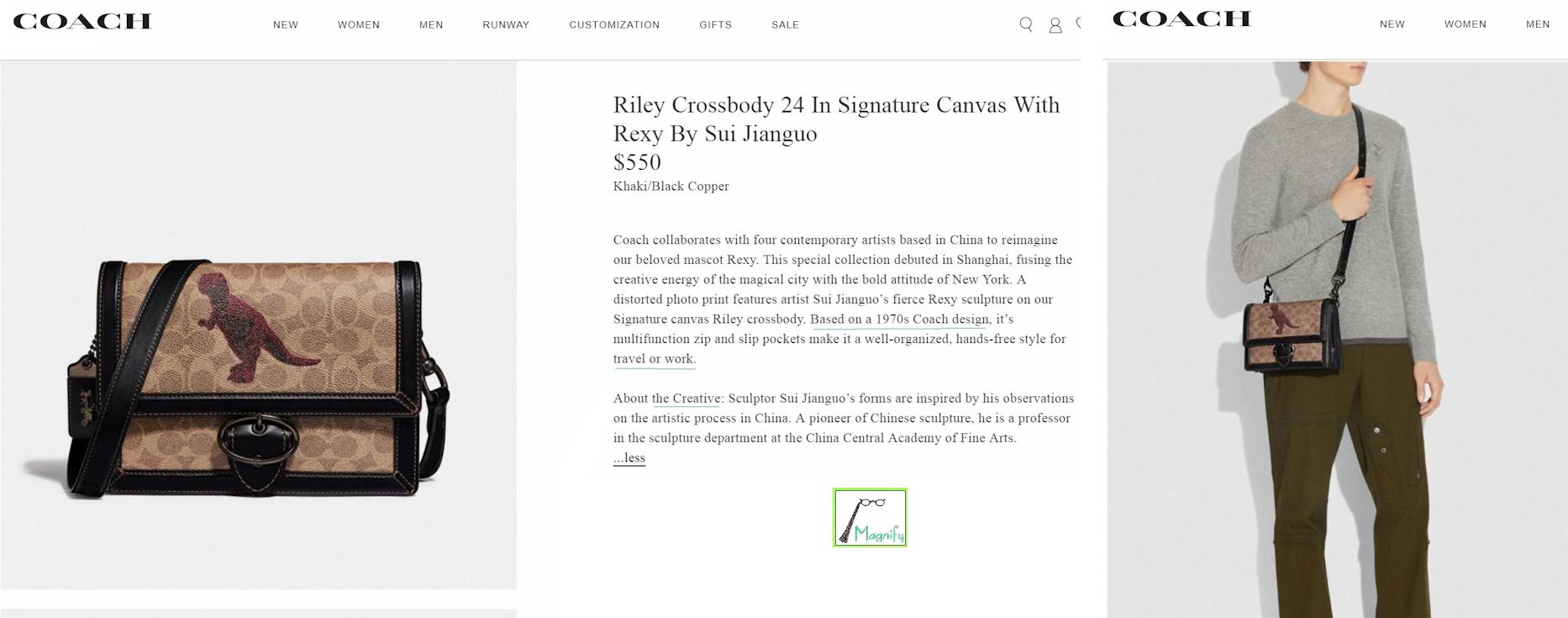

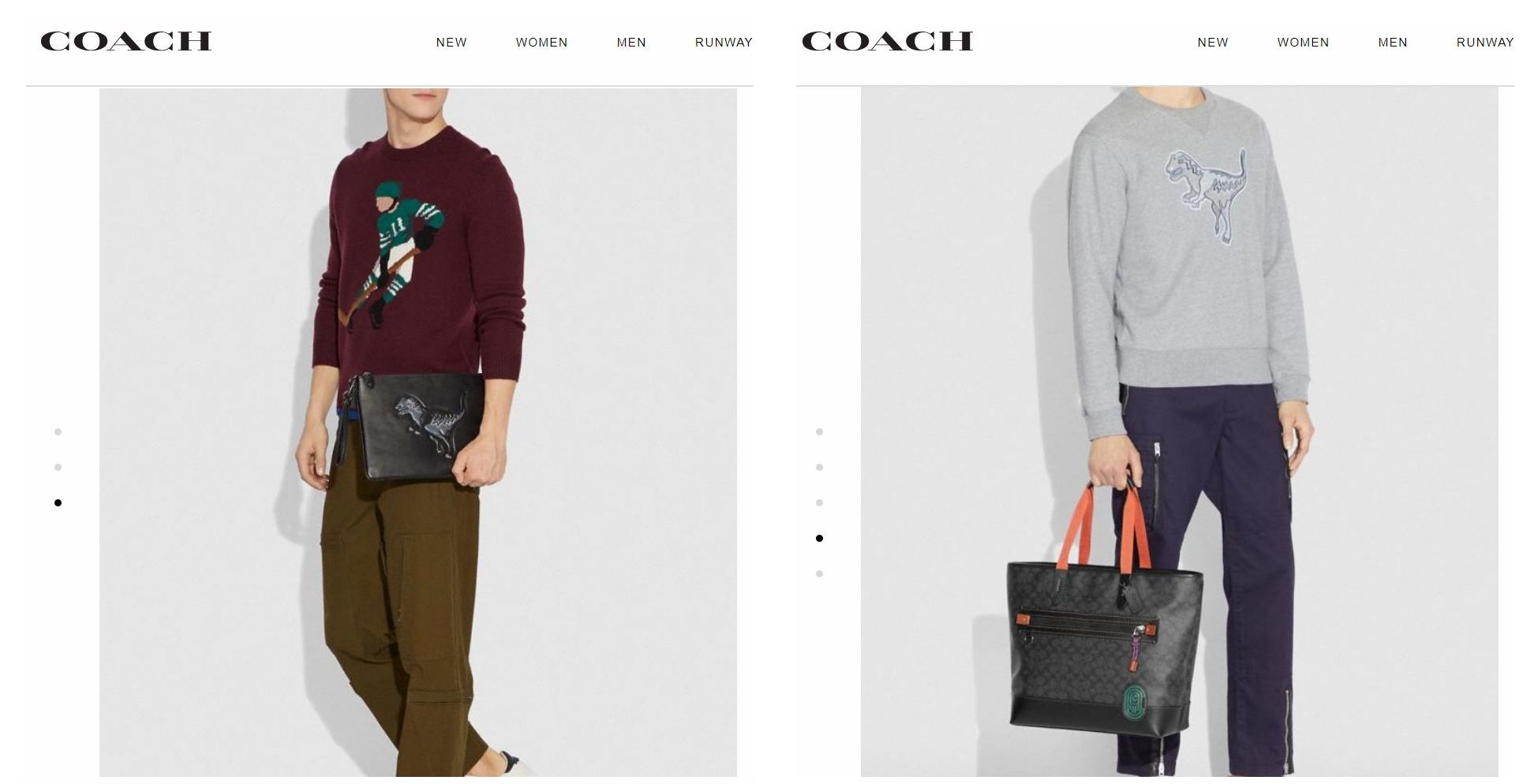

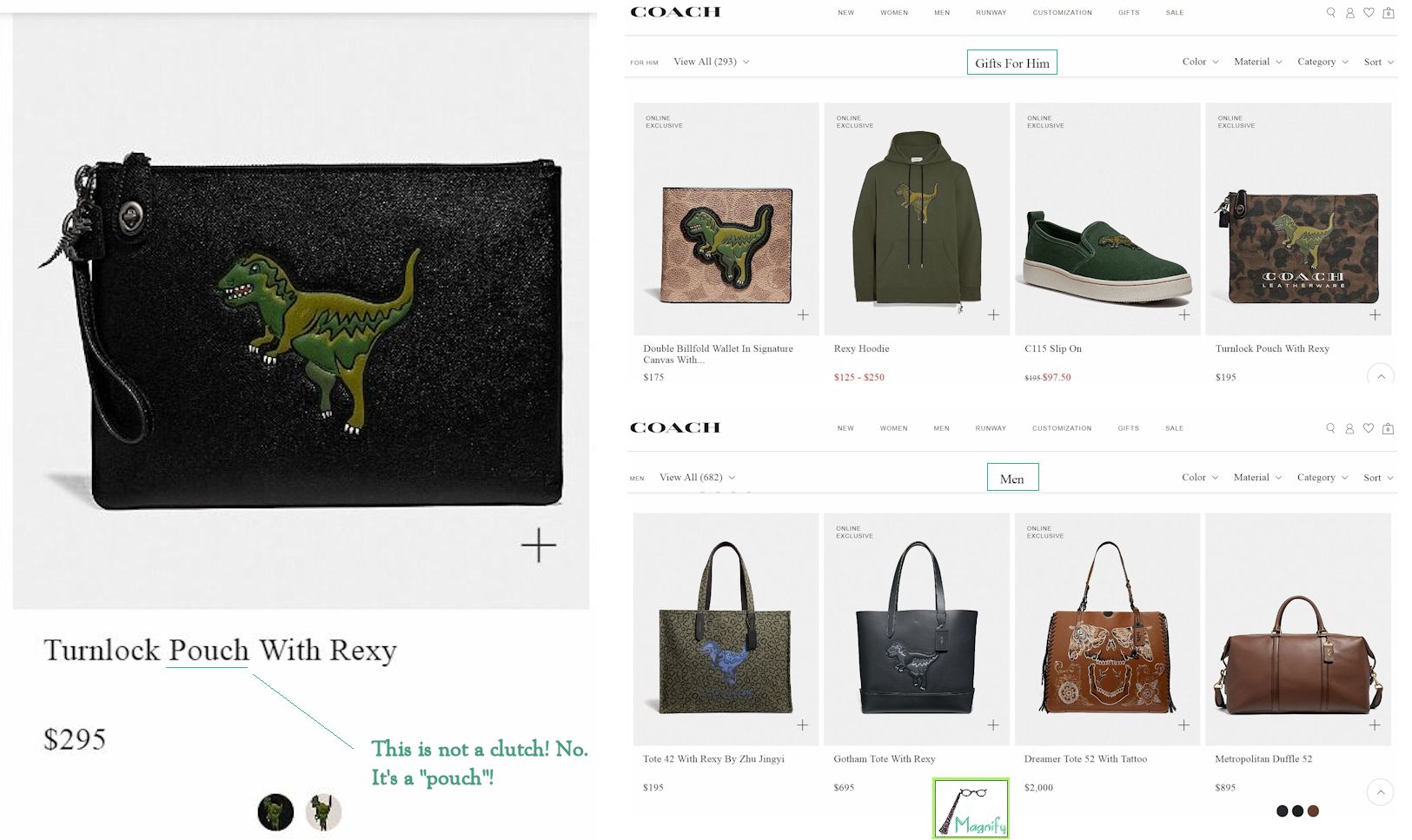

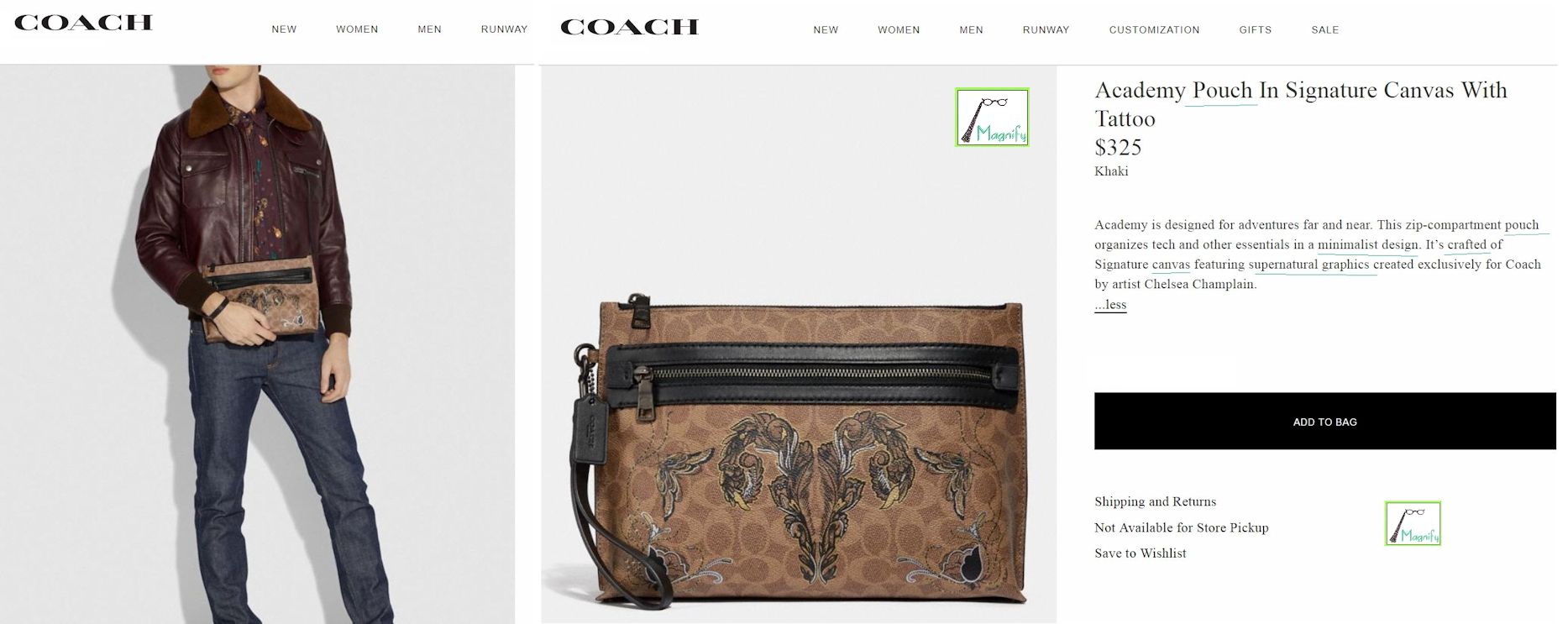

We don't want more Disney cartoons plastered on Coach bags. We want that vintage Coach quality leather back. And there are a lot of us who feel this way. (Not for nothing was Coach the most popular handbag maker in America for decades.) The advent of the new 'hug-it' creed seems to have increased these numbers even more, and brought things to a head. The entire extended Coven has convened and the verdict is in: this is the last straw. Get ready for it...the latest iteration of the Coach creed:

We know it's hard to believe, but yes, it's real, this is what new-Coach is up to these days, and it may be worth seeing it for yourself at a local Coach store to let it sink in. This has been appearing regularly enough lately that it seems set to become their new standard, the course being charted for the future of Coach, complete with a frankly disingenuous recapitulation of older 'hug-it' wording from 1970s Coach advertising. And while plenty of younger women found it sort of patronizing or just stupid, those with longer memories took an even dimmer view. The new wording seems to be suggesting that if only we'll just hug those stiff, plasticine bags hard enough, some kind of faux-grain split hides can be magically transformed into and behave like the excellent full-grain, full aniline leather of the old Coach bags. And that is seriously ridiculous, as anyone who ever held an original vintage Coach bag knows. (Are they proposing some new kind of leather-alchemy, or just gearing up for a future magical-merchandizing deal with Harry Potter, when the "Disney x Coach" histrionics have run their course? Who knows?)

As the wording of the new hug-it creed shows (Coach Leatherware stoops to "Genuine Leather"!?), it's high time we all understood exactly what that special old Coach leather was. We're talking the concrete materials now, how those bags were made and what they were made from. Because if the language of the new creed tells us anything, it's that we're on our own now in terms of objective metrics of leather quality. The old Coach used to focus almost exclusively on describing and explaining the leather used, as the mainstay of its advertising, and the old-school Coachistas --the original buyers who put the Coach bag on the map-- knew all this stuff.

But times have changed and the new-Coach/Tapestry approach is literally opposite...silent or euphemistic at best, advocating leather-alchemy at worst. Especially for those of us who have only the dimmest memories of those sleek yet soft and chunky leather Coach bags that the older girls and the grown-ups had, pre-2001 and before logomania hit, we really need to get up to speed because Coach/Tapestry has made it no secret that they're targeting us now. And some of us feel, targeting us like children (widdle fwowers! "iconic" Dumbo!), or 'snowflakes' (so anxious for everything to be "uniquely [our] own"), or maybe just plain flakes...unable to tell when quality materials are eliminated, so long as a prominent shiny brand logo is slapped on the front of something. It's for us they devised, just before this new 'hug-it' creed, "the Storypatch" as a "badge of authenticity."

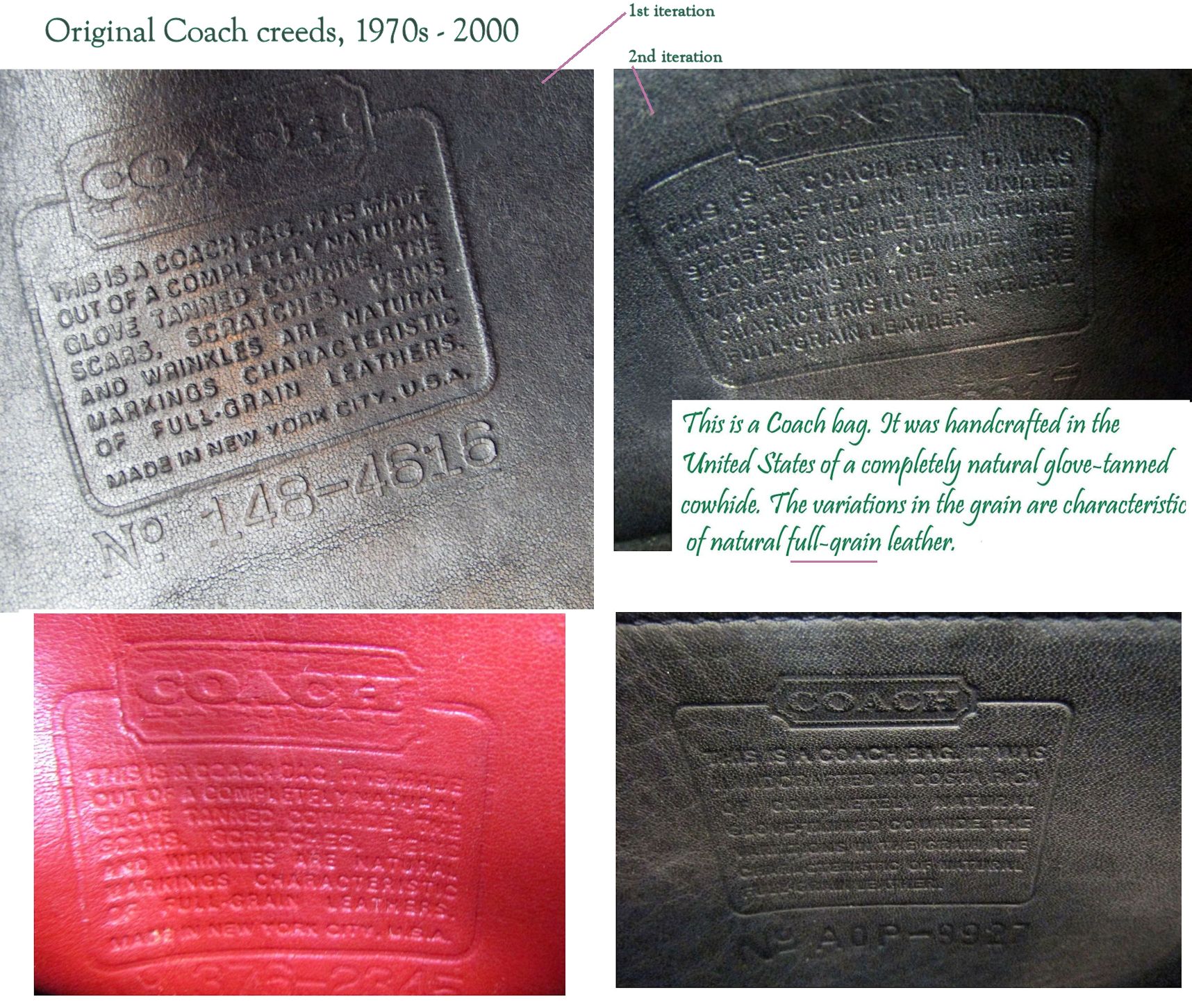

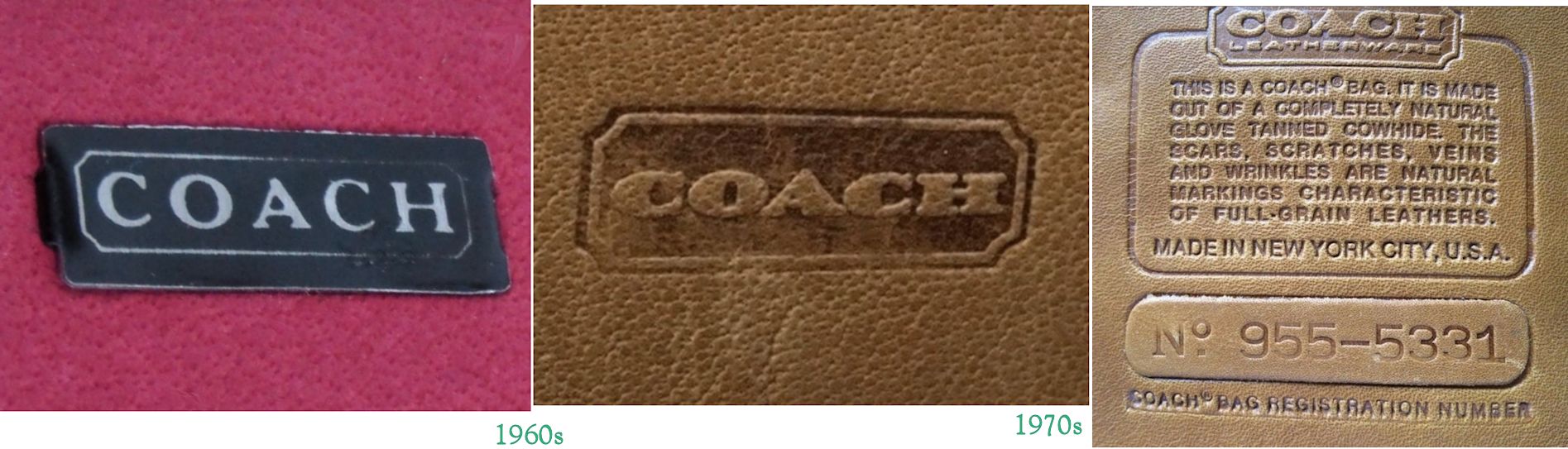

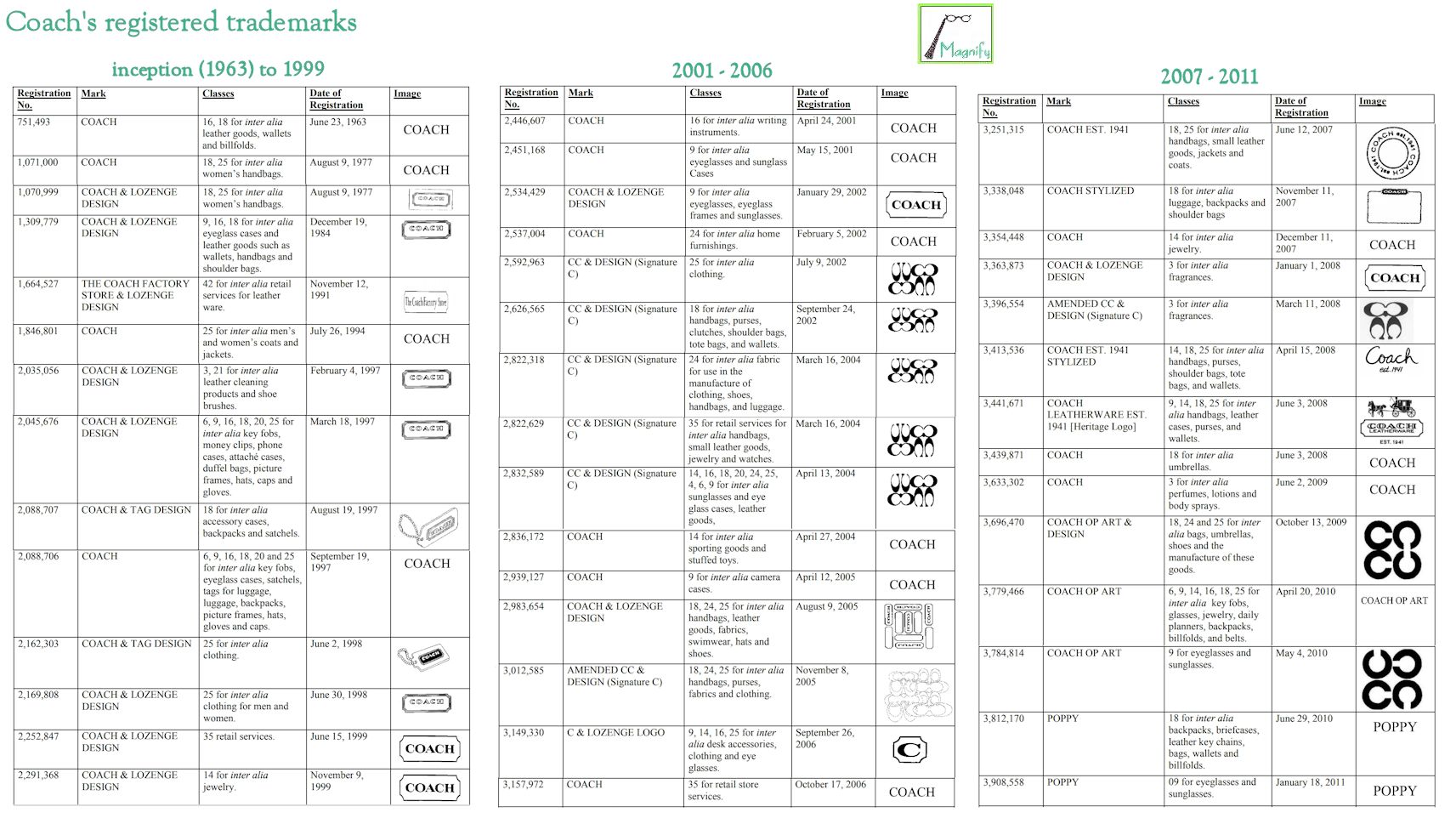

It is imperative to know, as the original Coachistas always did, that the primary purpose of the Coach creed was as a guarantee stamp, assuring buyers of concrete grades of quality leather. It was the company's way of warranting to the buyer that the highest quality materials had been used, thus the bag was actually worth the asking price. It is no coincidence that, prior to 2001, every Coach creed, from the advent of the creed stamp in the 1970s onward, contained the word "full-grain." It was guaranteed.

This is why people called it the "creed," which implies a set of beliefs, principles, a set of ethics -- a promise by the makers to uphold those ethics in their product, as the foundation of what that brand logo symbolized. And that is an entirely different concept of both branding and value itself. Where value is tied to concrete standards of quality, the brand logo is just a shorthand for that quality in the product. And so it always was with the Coach stamp. Until recently. When a creed becomes a "storypatch" (it's storytime, little girls!) and value is supposed to inhere in a logo stamp alone, no wonder it can be framed as a "badge of authenticity" -- because that much they'll still warrant us. Yes, it's really truly made in an authentically Coach/Tapestry-contracted factory somewhere in China, made of don't-ask by who-knows. But they can't tell the difference, they just want the logo because we're a designer-lifestyle-brand now. We'll cut quality and raise prices and have runway shows. It'll be great, like taking money from a baby. (Again, warned ya...screed.)

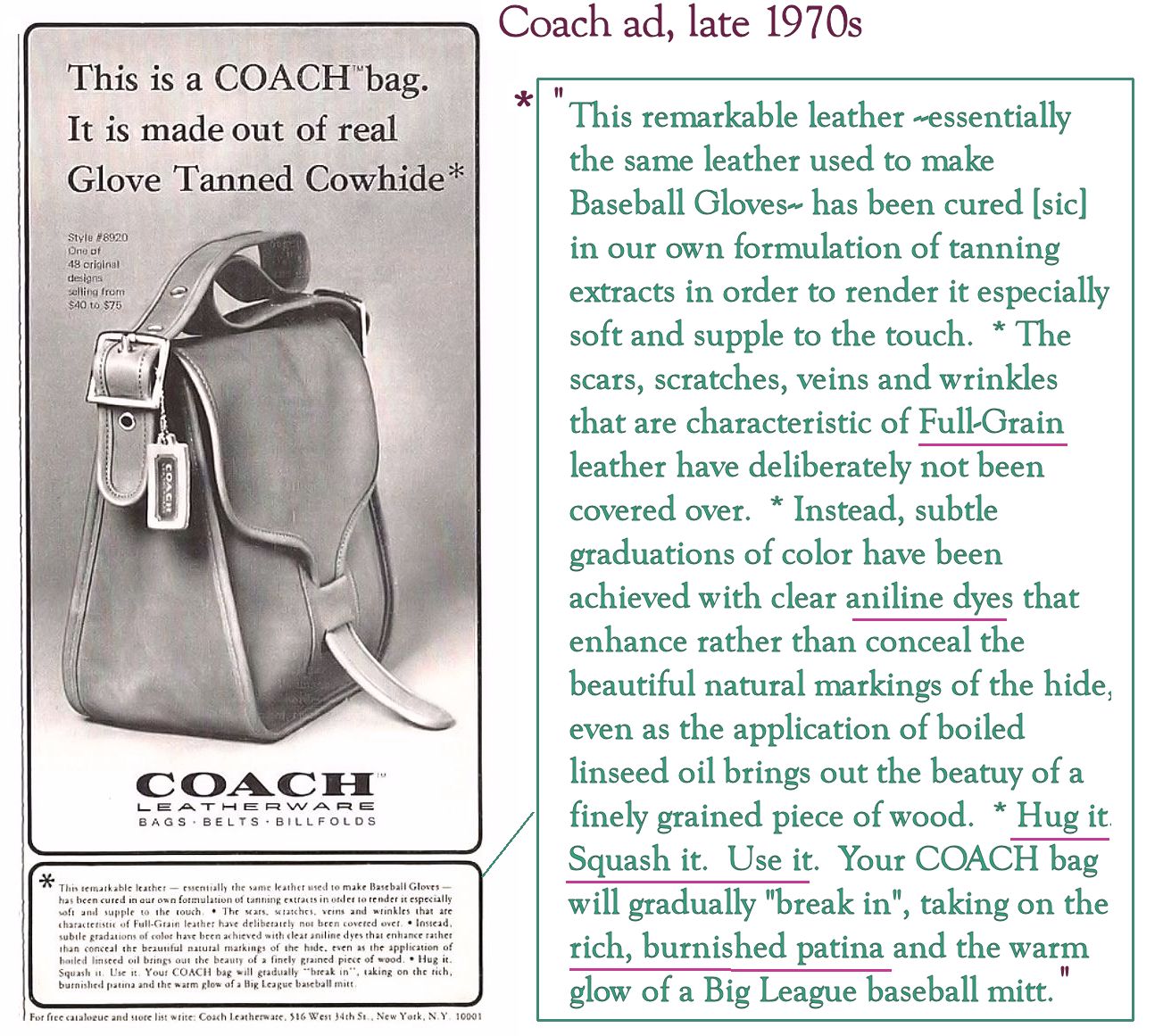

Let's review some vintage Coach ads to let this older and very different concept of both value and the purpose of branding sink in, beginning with some original versions of the hug-it language. Here's one, from the dawn of creed marking, describing the materials used c. 1975 in the Courier bag, along with 47 other Coach designs then on offer. The underlining is ours --note the concrete materials standards:

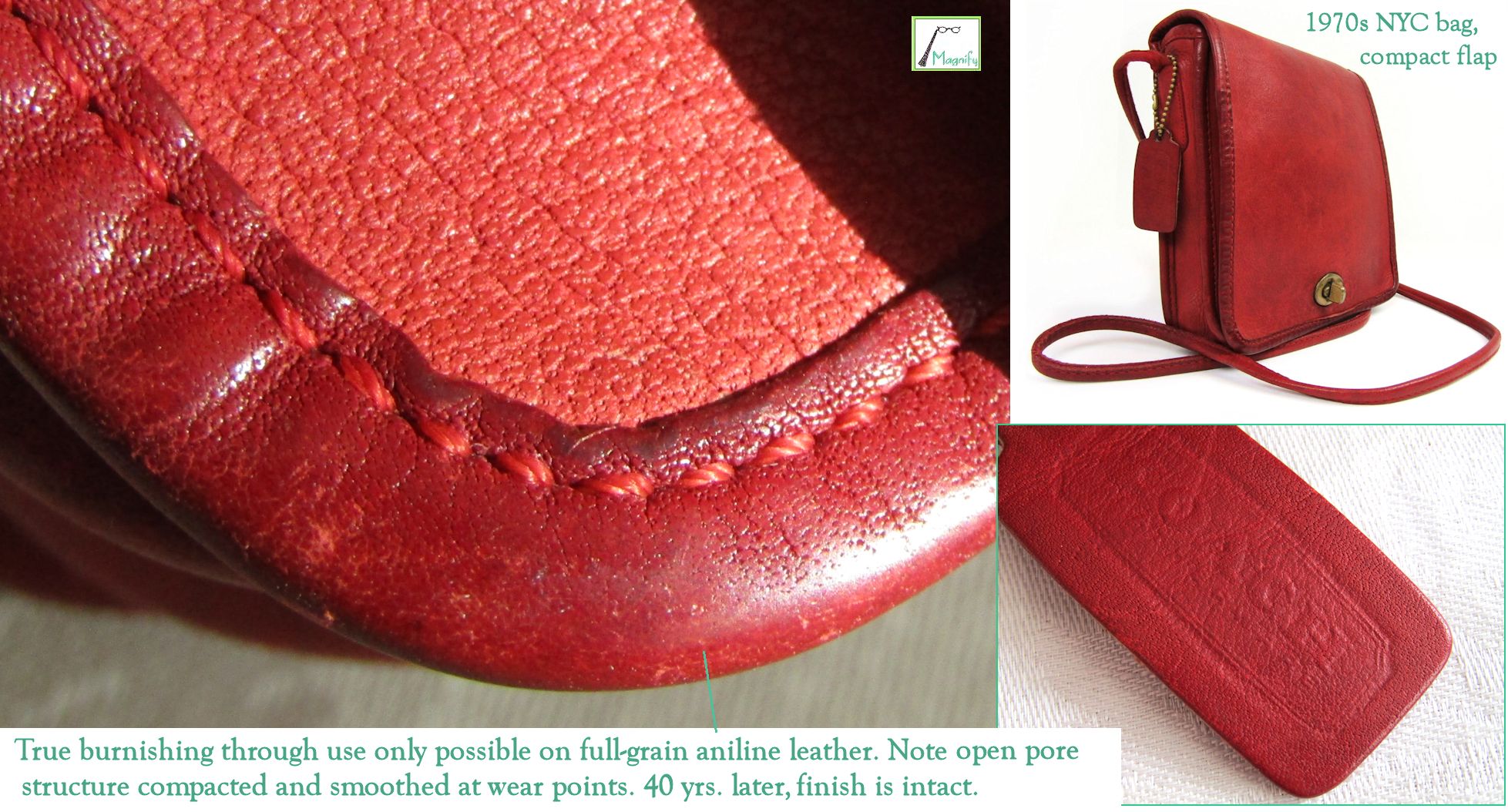

This ad, with many others, shows how the Coach company always explained their products' materials, and why they used them, as having a direct cause and effect relationship with how the bag would wear, actually improving with age. Things made with faux-grained and plasticized surfaces don't burnish. Instead their surface coatings wear through and show the physically and visually different substrate layers. This doesn't happen to old Coach bags, and that's why old Coach bags last. The burnishing and softening of the surface is a natural property of natural leather. There's a lot of flim-flam in the modern marketplace, but the facts are pretty basic.

1) The old Coach leather burnished because it was not coated with paint and plastic.

2) Only leather through-dyed with aniline dyes is not so coated, but left open or 'raw.'

3) Aniline dyes can only be used on full-grain hides.

4) All old Coach bags were full-grain -- and that is why they burnished and became 'uniquely your own'.

A full-grain leather is the real grain layer, the natural skin surface, so that when you're looking at a piece of this leather you're actually looking down into the grain, same as looking down into the grain of a piece of wood. This is totally different from a mechanically applied imitation grain pattern of one kind or another (stamped into a suede surface, layered with opaque paint, sealed with polyurethane, etc.).

Aniline dyes are translucent, clear like a stain, rather than opaque like a surface paint. They camouflage nothing. Only full-grain leather is aniline dyed for the same reason that only good natural wood is oiled or stained. Particle board is never stained, but only coated with paint or covered with fake-wood-grain decals, because that's an attempt to hide the fact that it's particle board and not real wood. The coating of modern leather products follows the same basic pattern.

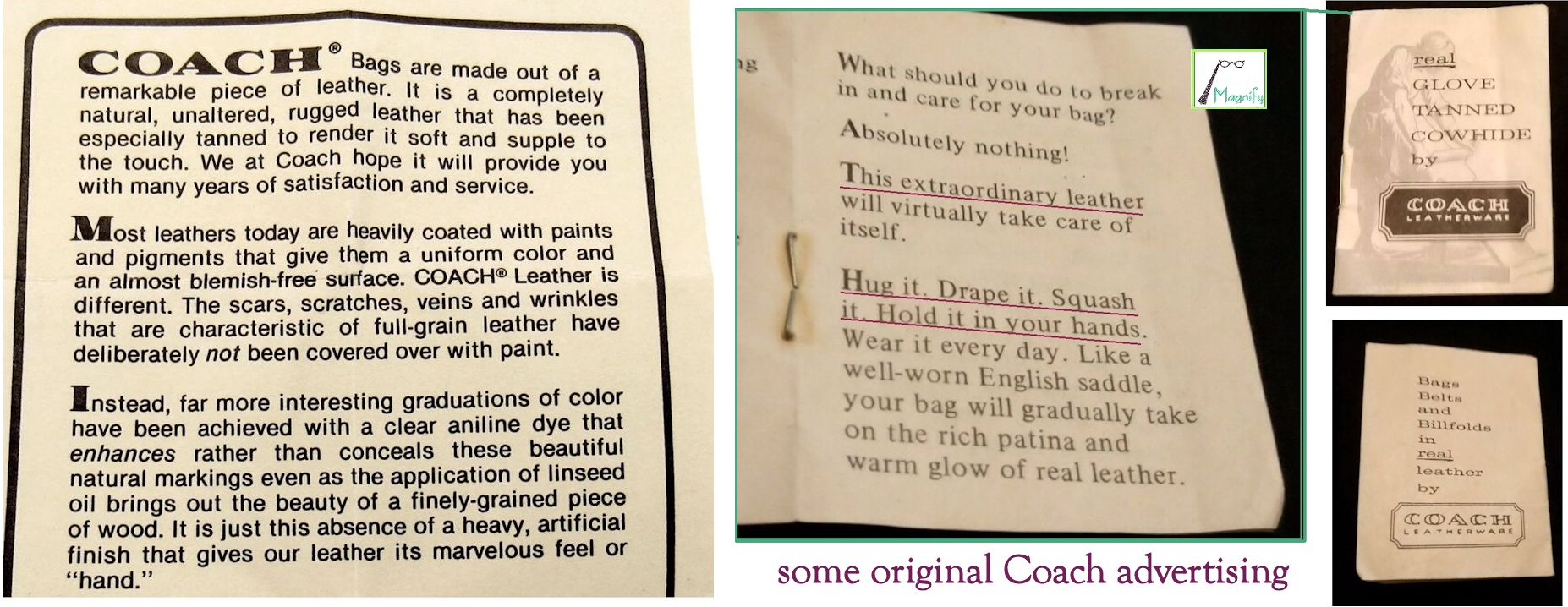

Below are some typical inserts that came with new Coach bags through the 70s and into the 80s, again with the earlier hug-it language. Here, the buyer is told that "wear[ing] it everyday" is what causes a patina to develop over time on uncoated natural full-grain bags -- precisely because they're not coated with paints and plastics.

What the 2019 creed very vaguely, even euphemistically calls "a character that makes it uniquely yours" is defined very differently, far more concretely, and frankly more realistically here as "the rich patina and warm glow of real leather." And there it is, in a nutshell: back then Coach made bags of what an ordinary person would legitimately consider to be "real leather." This was the brand's claim to fame. We can see how that cause-and-effect relationship between the specific quality materials and bag longevity and patination was framed with original Coach. Clearly, the buyer was not being encouraged to attempt leather-alchemy back then on a substance no reasonable person would ever imagine as "leather." But unfortunately that's what "Genuine Leather" means these days, as we can see in one of the more common hide-stratification diagrams showing how cowhides are split into sheets and processed.

The point is, the surfaces of Coach's older leather bags really were the best grade of leather out there, full-grain full aniline, and this is why just about all of their advertising focused on describing the leather back then. The specific grade of leather was what always distinguished a Coach bag, because nearly all other handbag makers --again, both back in the day and even more so now-- used lesser grade hides with one or another kind of faux-grain machined/painted/plasticized surface.

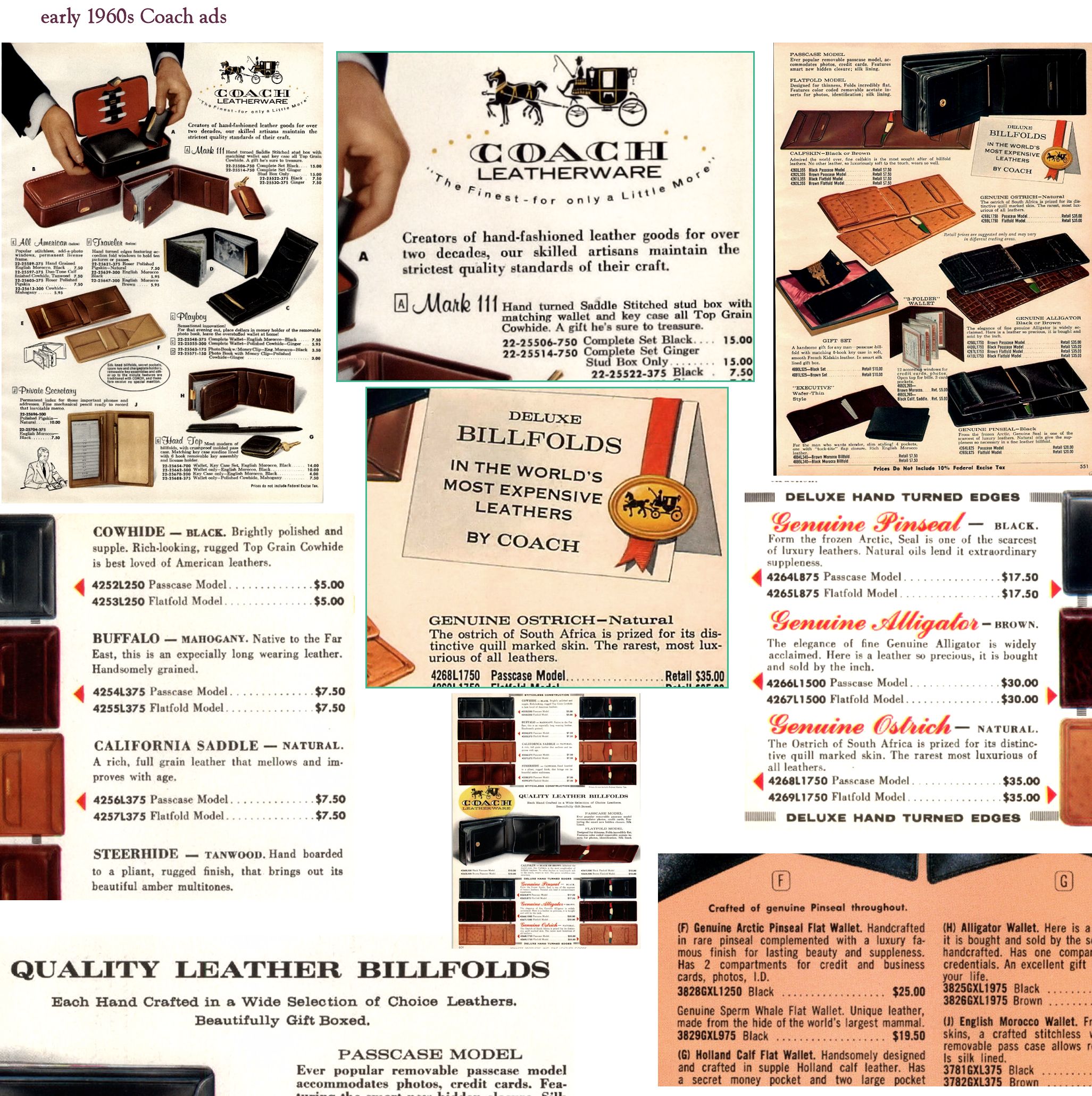

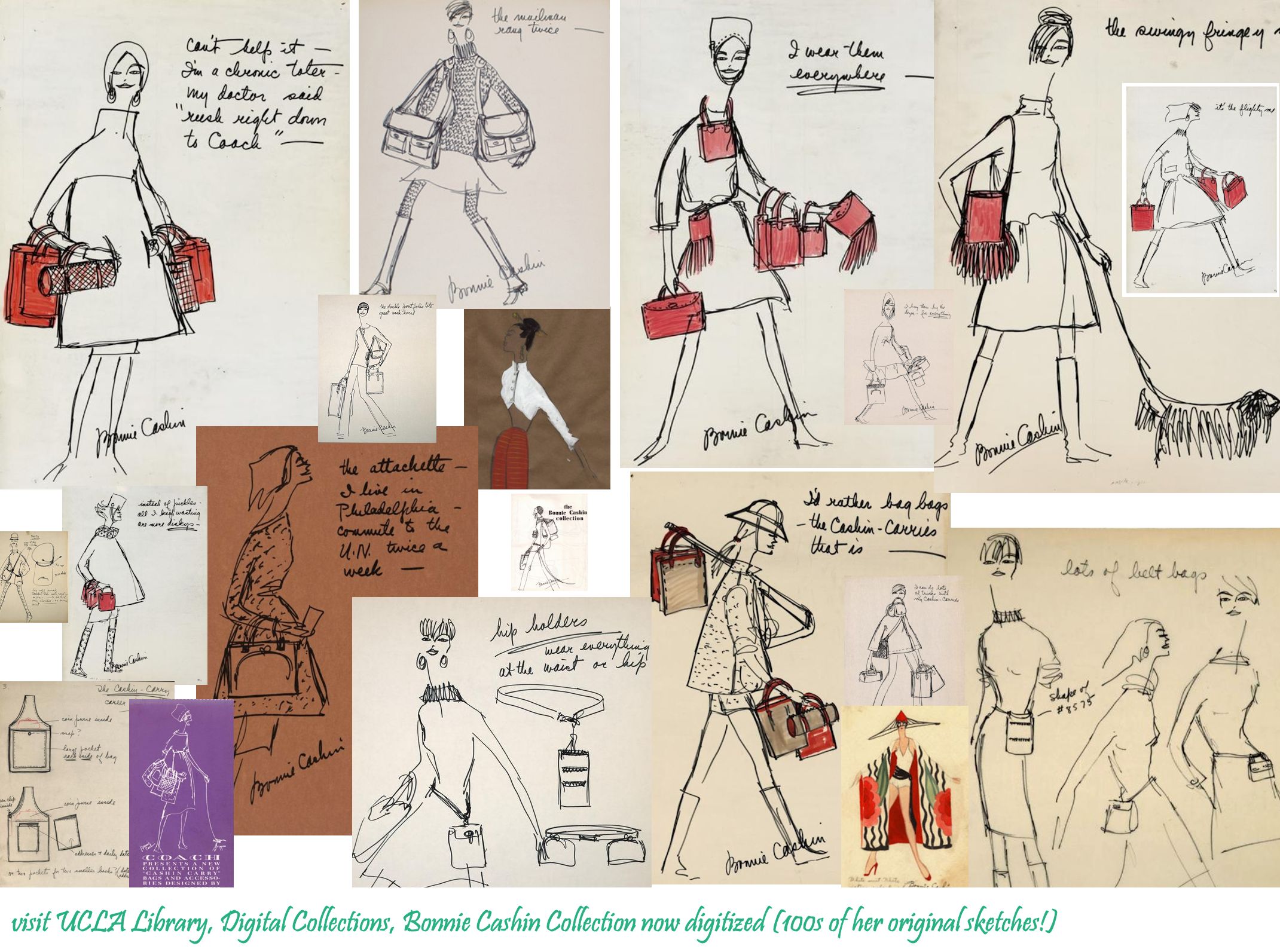

The original Coach company, even when they were a wholesaler of men's wallets, simply never got involved with faux-grains, sanding, or in general covering up the natural markings of the hides they used. They were a leathercraft company first and foremost which, in the early 1960s, became a maker of handbags under the leadership of Miles and Lillian Cahn, and with design by Bonnie Cashin. No matter where we look in the brand's history and marketing, we see one consistent theme: natural, quality leather.

This almost single-minded emphasis on leather quality dates to the Cahn's early ownership of the company (bought out Gail Leather/Gail Novelty in 1961), which we can see from the early 60s ads below, especially the tag line, "The finest...for only a little more". It was when Miles and Lillian Cahn took control that Coach as a (retail) brand began, and began to develop its own special character. That character was always based on superior leather. (It's worth noting, the 1941 date so often heard today actually marks the proto-Coach operation, Gail, which was a wholesaler of men's small leather goods, mainly wallets and billfolds, originally part-owned by Miles Cahn's father. Miles was fighting in WWII in the early 40s, returning home and beginning to work at Gail only in 1946. Both he and Lillian knew the craft of leatherworking, and had their own separate company for years prior to buying out the (Gail) factory owners and launching something we would recognize today as Coach Leatherware. We'll have more to say about this shortly, but it's worth stressing that there would simply be no Coach bags without Miles and Lillian Cahn, and the Cahns' focus was always on ethics and quality. This screed was largely motivated by respect for them, and for Bonnie Cashin, because that respect is due.)

As we can see from these oldest of ads, especially when compared with competing 60s brands of wallet that stressed things like space-age materials, Coach always dwelled solidly in the realm of well-crafted and valuable grades of leather. In fact, it was a branding strategy almost totally focused on using and explaining quality leather, even well before Miles struck upon using baseball glove leather, and marketing the concept of "glove-tanned." It was understood then that the target consumer --male or female-- could both recognize quality materials, and recognize the absence of them in competing brands. Everyone was assumed to be a sensible person. (It would have never occurred to a company like old-Coach that those better materials would one day be removed from its own products, while the price was increased, yet their absence would not be detected by the buyers...but we'll get to what a different kind of company Coach was under Miles and Lillian Cahn shortly.) Whatever we might think today about 'exotic' leathers made from the hides/skins of many non-cattle animals, in terms of changing values like growing feelings of animal solidarity and desires for environmental protection, there was always a focus on using natural materials, in a natural state, and describing concretely what those materials were. It was a very different world in the 60s, and there can be an ick factor to modern sensibilities (seal? whale leather...really?), but there was an accuracy to the ads that is missing now, as well as an emphasis on quality paying dividends in greater longevity.

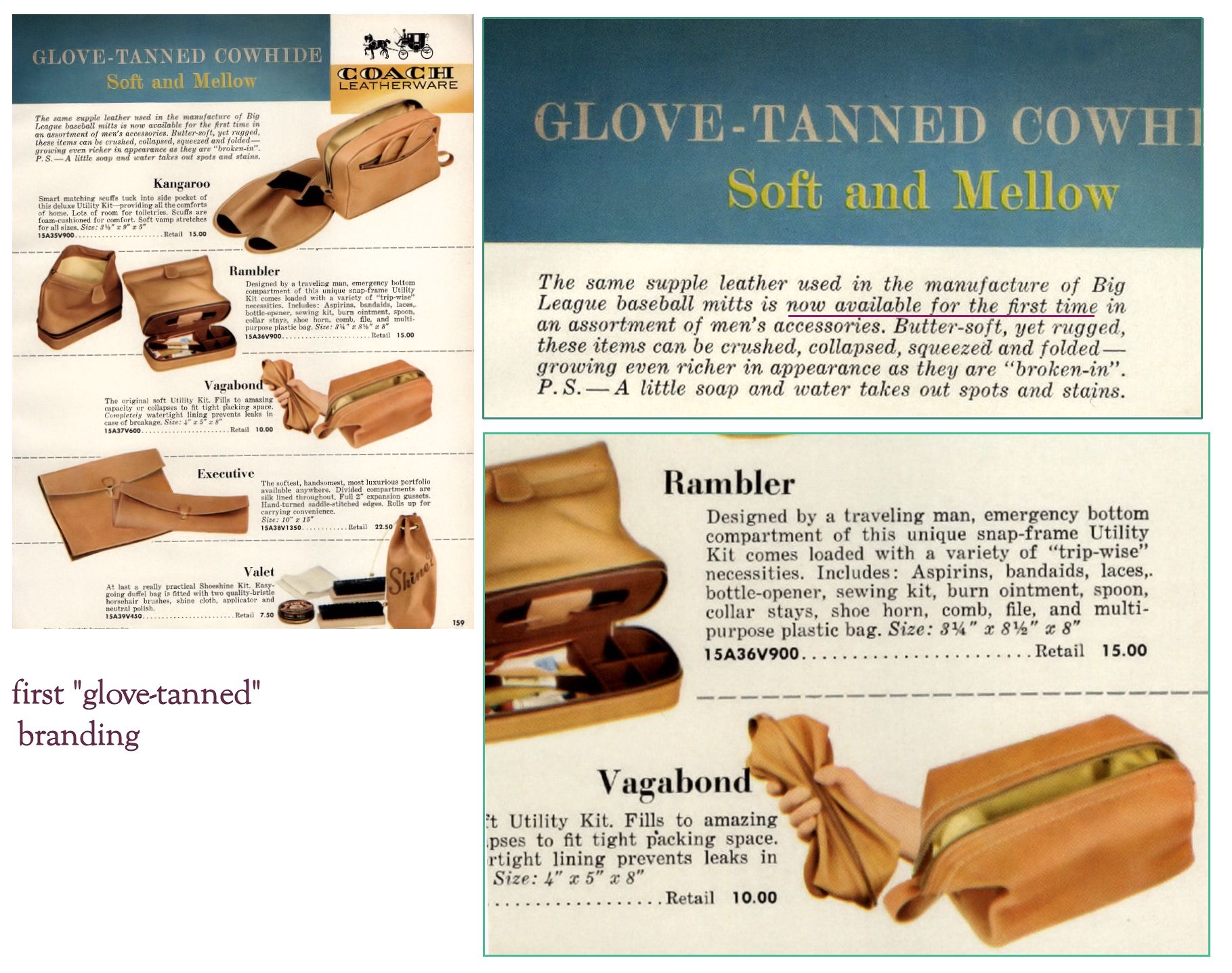

There was always cowhide among Coach's products, and it was always full-grain (which was known as Top Grain back then --we'll get into why in a minute). With the advent of the marketing concept of "glove-tanned," first seen in the early 60s men's line (see ad below), Coach presented it in its usual matter-of-fact way, by describing the leather itself and its origin in detail. Unlike new-Coach marketing, the old Coach ads always used concrete terms, with an honesty about them, promoting things in a particular leather on the basis of how it behaved --notice the hand grabbing and crushing the toiletries case-- and how the type of leather used actually enhanced functionality and product life-span. Because that leather actually was very good and it did behave as suggested, people liked those small cases made from it...the Cahns had struck on something here. The traditional tannage used for cowhides destined to be baseball gloves, next employed in making handbags (making women's handbags was Lillian's idea, as Miles was always proud to explain) soon took off. Finally, after about 15 years of struggle by this small company, they had something that no one else did, and it was being noticed. When they then asked (already very famous) Bonnie Cashin to design a line of handbags for them, and she agreed, the Coach bag was born, its future assured. That special cowhide quickly and completely displaced the exotic hides and skins from the Coach product line for many decades -- again, until very recently.

It bears mentioning that cows never were, and never are, killed for their hides. Instead, cowhides are a byproduct of food production and, until we've all stopped eating steak and burgers, there will be cowhides traded on the international commodities exchanges. The cowhides would be destroyed if not tanned into leather, but this isn't the case with the skins of most other animals, some of which are never eaten as food. One of the starkest cases of non-food-animal skins is snake skin, so it seems far less forgivable when 21st century Coach uses snakeskin today, recently become common as a trim. Notice, too, they can trouble themselves to call that "genuine snakeskin" (we haven't seen these bags in person yet, it appears to be dyed sea snake, not python, etc.), and it's anybody's guess what "refined leather" is. But worst of all, they're using this snakeskin in what we think is the most wanton way, as not only are the snakes being killed for their skins (not byproduct of food), but snakeskin is by its nature a very fragile material. Using it on the handles, of all places, amounts to bags that are essentially made to fail, meaning not just that snakes were killed for it, but killed in vain, as those new bags are already halfway to the landfill, based on serious design flaws. (Several of us sell vintage furs, in an attempt to coax people away from buying new fur and thereby supporting the modern fur industry, so we have to rant a bit about not killing animals of our own era for comparatively frivolous reasons. Yes, even non-cuddly animals that many humans fear, like snakes. Many humans fear dogs, too. Would anyone suggest this fact makes the dogs not sentient beings?)

In any case, what we see from the earliest ads is that Coach was always about the quality of the leather. The advertising always detailed to the customer exactly what that leather was. And the leather was always put to use in ways that didn't squander the hides, but instead employed them to make very functional objects that would give many years of service and could --very often did-- literally last a lifetime.

When we look at the hug-it language of that earlier period, it's clear it was meant to reassure the buyer, you don't have to baby this bag or carry it like some fragile porcelain orchid, because these bags are made well enough, and made of good enough materials, that you can safely use them without them wearing through or wearing out as things with mere surface treatments do. And as you use these bags, because the leather is the best, they will become more supple, develop more depth, take on that tactile character that only natural leather can. "Hug it. Squash it. Use it. Your Coach bag will gradually 'break in,' taking on the rich burnished patina of a Big League baseball mitt." The individual quality and longevity of a Coach bag flowed as a direct consequence from Coach's use of natural full-grain leather to construct the bag.

That was why they used the best quality leather. And now they don't. See the problem with the new 'hug-it' creed featuring, not "full-grain" anymore, but "genuine leather"? There's a reason the latest bags look and feel like plastic. In a year or two, when they've behaved like plastic and ended up in the landfill, it won't be because they weren't hugged enough.

Putting aside what we may think of the aesthetics of leather bags with decal-like cartoons and twee printed florals, the issue that concerns us here is basic leather quality, as determined by its physical properties and processing. Back in the day, before the advent of modern splitting machinery and synthetic polymer coatings, leather was easy to define as the depilated (de-haired) and tanned hide of an animal, usually cattle. Initially it was all full-grain, simply because there was no mechanical process to simulate a smooth grain-like surface from any other part. If it was used upside-down, with the fuzzy underside as the surface, then it was suede, but still an intact hide, defleshed or scraped by hand. But that's over now, and has been for a century. With a few exceptions (some vegetable tanned leathers for specific purposes, industrial strength leathers for machinery, etc.), all hides are split or sliced into thinner horizontal sheets or layers now.

The initial practice of splitting was into two layers or halves, and terminology from this older method is still around and fairly common in the industry (and on the internet). It produces confusion, though, because it makes it seem there is a double meaning for the term "Top Grain." It's best to be forewarned about this, as the modern meaning of top-grain indicates the 2nd tier of quality, basically with the top layer sanded off. This is very different from the older meaning of Top Grain, when there were only two halves --not three or four layers-- possible from each hide. In the older splitting process into halves, you had the top, which was the grain layer, and the "drop split," which was the bottom portion, the inner part of the hide closer to the flesh or adipose tissue and having a suede surface on both sides. The grain layer was the good part, made into smooth leather objects, and the "split" (that underside or weaker portion) was markedly inferior and sold by tanneries for other purposes, the best of which was suede.

If we look again at the typical schematic rendering of leather layers (above), we see that the days of a simple top/bottom splitting of cowhides are gone. The vast bulk of today's smooth leather (i.e., everything other than suede) includes a variety of fairly unnatural surfaces, made possible by modern machinery and resulting in a hierarchy of grades of quality. It's possible to get more horizontal sheets or "splits" out of each hide now, but they're never comparable to the quality of the natural skin surface, and that surface is the grain: full-grain. Extending from the exterior surface to the corium junction, full-grain leather means the whole grain layer is intact. This is always the most expensive, especially when clear or not marred by damage, 'range marks,' etc. The reason isn't just the naturalness of the surface --this is of course what everyone imagines as leather-- but it's also an issue of strength and longevity. We can see that the area of the upper skin is the densest in terms of fiber structure, as a function of biology (thickest skin on the outside), the fibers actually forming a sort of crosshatched bond with each other. This is different from the fibers found below the meeting point of the grain layer and the corium, where the fibers become looser and lay more horizontally. This basic structural difference is why it's very difficult to tear a piece of natural smooth leather --the grain layer-- but much easier to rip a piece of suede, which is made from those looser fibers closer to the flesh. This basic structural difference is why the grain has always been valued more highly than any lower layers left over after the grain is removed.

The grain layer may vary in thickness, as the hides are now fed into large and carefully calibrated machines with rollers and blades. Just about any thickness (measured in ounces) can be precisely cut from each hide, meaning you can have thin and light full-grain, as seen in Bonnie Cashin's 60s Coach bags, or thick and meaty, like the 70s-90s bags (some of which were 8 oz. or so, a full 1/8" thick, where typical garment/accessory leather is only about 3 oz.). The advances in splitting machinery also mean it's possible to get more layers out of each hide now, and those additional ones won't be full-grain (there's only one surface per hide), but even weaker multiple split hides. And this is another reason splits are cheap.

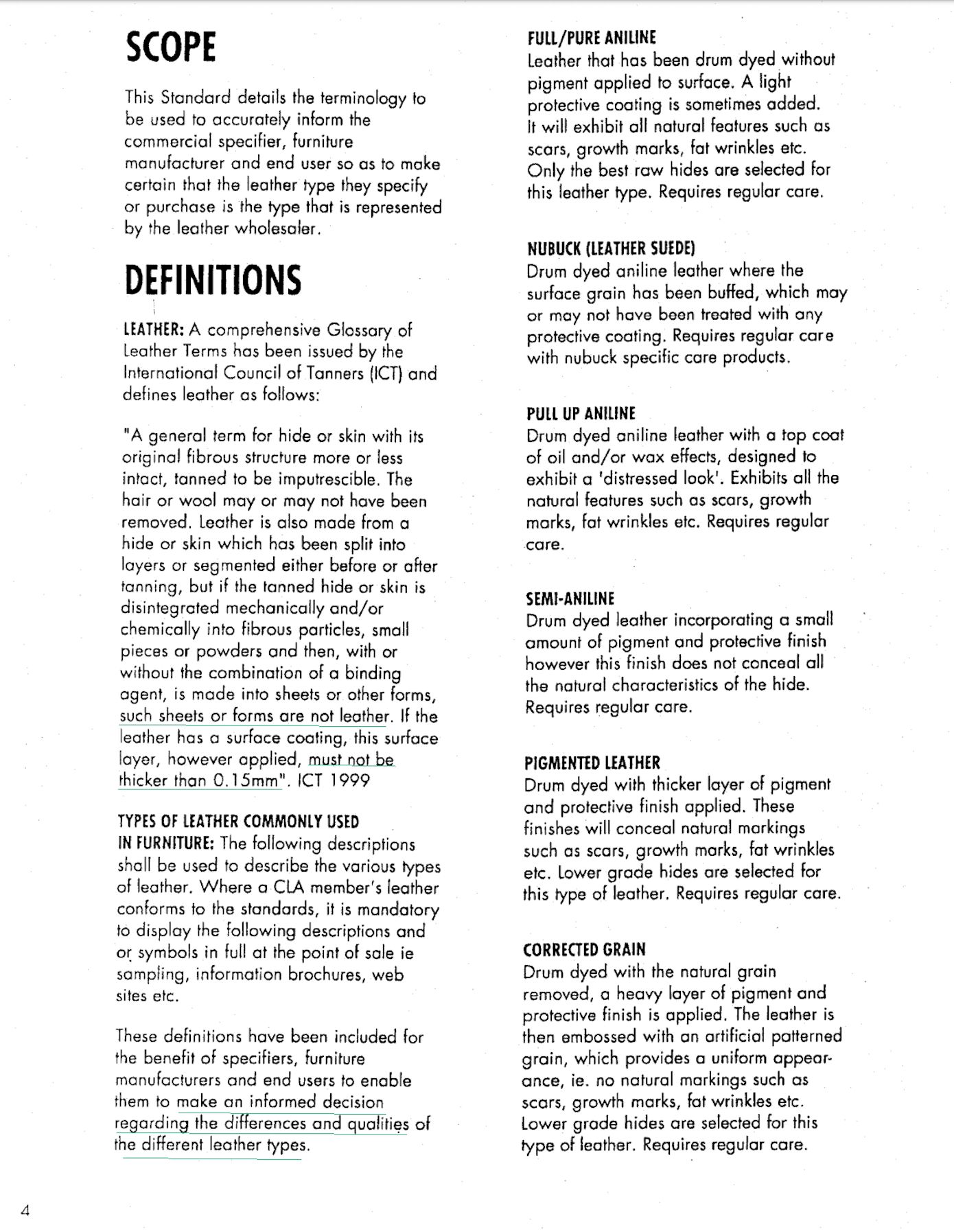

So the basic levels of leather quality you usually hear are:

1st tier: full-grain -- the natural grain surface, not monkeyed with or adulterated

2nd tier: top-grain -- part of the grain layer, but imperfections sanded off the top, then coated to look smooth

3rd tier: Genuine Leather -- made from the drop splits, those lower suede layers, even more processed to look smooth

4th tier: bonded leather -- various % of leather shavings or pulp mixed with synthetic polymers (i.e., total crap)

If Coach leather bags were all still made entirely from full-grain hides --as they used to be-- we could just stop at the 1st tier and not worry about the rest. But now that "genuine leather" is appearing in the creed, those days are gone and delving deep into the details of modern industrial production processes for making what we consider 'frankenleather' has become necessary to even know what you're buying. (This is another reason we're angry with the new Coach. It used to be so easy.) We'll mostly ignore the generally repulsive 4th tier, "bonded leather," because it's basically a slurry of plastic with a handful of leather shavings sprinkled on the back and doesn't deserve to be called leather at all. We'd say just avoid it, it's a scam. (It's basically illegal to call bonded leather "leather" at all throughout the EU and in a number of other places. What now passes as "Genuine Leather" in the US is also not permitted to be called "leather" in a variety of other countries, and it can mean a few variations in manufacturing technique, but frankly it's never good, and almost always involves split hides surface-coated with a thick layer of something synthetic and non-leather.) We'll deal with full-grain first here, just because it's the only one that's really a natural smooth leather these days, then move into what the newer meaning of top-grain (2nd tier) is.

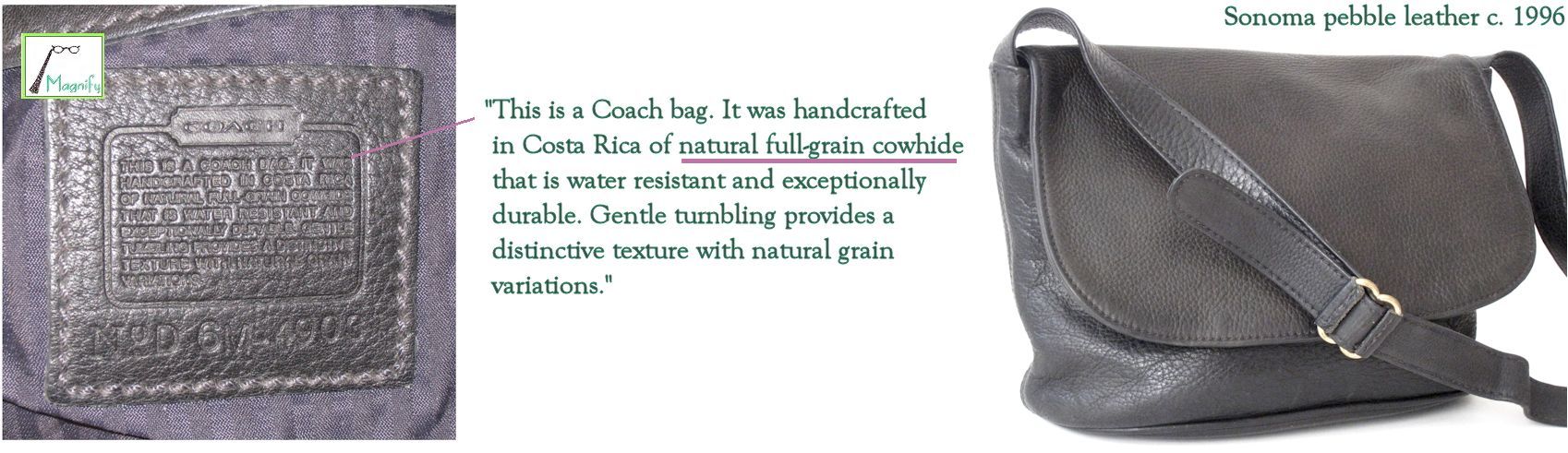

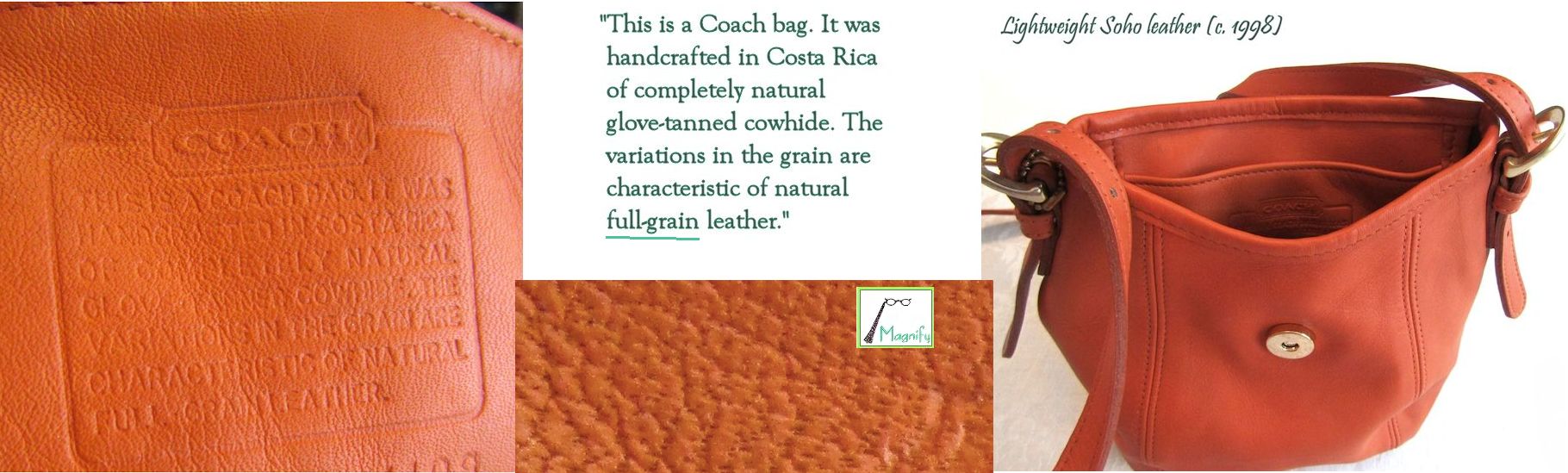

Full-grain is the least altered or least machined leather you can get. Possibly the most obvious definition of the full-grain leather used in all vintage Coach bags is to be found in the wording of the original creed itself. That description, combined with the warm, satiny surface you found the bag to have, and the visible lack of any flaws seen in lesser leather objects (e.g., no marring "range marks," no weak or thin areas, etc.) showed it to be a good grade of full-grain. There were two iterations of the original creed (see below), the first introduced in the 1970s and appearing into the 1980s, and the second appearing after production had expanded beyond the original NYC factory, first to other locales within the US (1980s), then to a few foreign countries through the 1990s. (In our experience Costa Rica appears the most frequently in the 90s, but it should be noted, the Costa Rican-made bags are actually just the same in terms of quality materials and fabrication as the USA-made ones of the same period. This is in distinct contrast to the lesser grades of full-grain in use after Coach was spun off by Sara Lee and production was moved to China in 2001.)

The earliest creed told buyers: "This is a Coach bag. It is made out of a completely natural glove-tanned cowhide. The scars, scratches, veins, and wrinkles are natural markings characteristic of full-grain leathers." And in some ways, this is all you had to know. It was, in essence, their guarantee that it was the best grade of leather because only the very best cowhides, or sections of cowhides, look like those seen in old Coach bags when they are left completely natural. Look closely at any vintage Coach bag (vintage = 20 years old or older) and it rapidly becomes clear that the only irregularities you'll find in the surface are just that, natural markings, of the type that arise from the physiology of the individual cow, like light fat wrinkles or veins. It's this aspect that makes each hide slightly unique, having an almost wabi-sabi quality, the slight variations or heterogeneity seen in all products of nature. Yet one never sees serious blemishes or damage in any hides used by Coach during the era of the original creeds because quality control was strict. Coach selected the best full-grain hides they could get, and used only the best parts, because they were a leathergoods outfit above all else, and this shows to this day in the surviving bags. Between us all, in the thousands of Coach bags we've bought, sold, carried, traded, hoarded or coveted over the years, never once has any one of us seen a marring "range mark" (i.e., mark from where the cattle was branded, serious scars from barbed wire, etc.) on any hide used in an old Coach bag. When it came to the leather, corners were simply not cut.

So vintage Coach bags were not just natural full-grain, but only the best portions of each full-grain hide were used, with no flawed pieces hidden in gussets, side panels, straps, etc., as was done by some other makers of bags in order to conserve on materials and thereby cut costs. Coach bags stood out in this regard. Only 1% to 5% of the cowhides coming into tanneries can ever be made into full-grain leather at all (and especially full-aniline, which again, conceals nothing), simply because only that small fraction are in good enough condition. To be free of serious surface blemishes, holes, heavy range marks, butcher or tannery damage is rare, so those clearest hides are generally selected to be used for full-grain -- that is, for purposes where that natural surface will be visible in the end product. The vast bulk of hides have too many problems, if not in one area then in another, such that most are destined to be used for tannages that allow for covering up of these things by sanding them down, concealing with paint/polymers, etc. (i.e., top-grain/corrected grain), in part because people have been conditioned to expect complete uniformity in leather now (despite the fact that this is not, and never was, the true nature of leather). Only the best cowhides are clear enough to be left natural and uncoated, meaning full-grain is the rarest, most desirable, most expensive to work with.

Within that fairly small category of hides acceptable for full-grain tannages, they're further sorted from there, from almost completely clear and with just a few fat wrinkles or other natural irregularities, through small range marks of a given number in a given section, down through visible brand marks, holes, or butcher or tannery cuts in the more important sections, like the bend or butt. Different tanneries use different grading systems (1st, 2nd, or A grade, B grade, etc.), often with range marks/irregularities categorized by severity and number within a certain percentile. No single hide is ever perfectly free of all irregularities, because it's a product of nature, but it's common to have batches graded and sold within those percentiles, as with TR, "tannery run," which varies somewhat with each tannery, but usually means you'll get an average in a batch, say 50% Grade B, having three or four defects in the best areas of the hide, then equal portions of Grade C and Grade A, say 20% each of those (grade A having only one or two flaws in mostly secondary areas, grade C having big problems in key areas meaning a lot of waste), then sometimes there's a final 10% of scraps or "utility grade," filler stuff with really heavy damage. The grades boil down to how much of each hide is usable, especially in the prime areas or cuts, and how much will be waste, once you start cutting out sections for things like making bags.

The chart above shows a couple of the many ways tanneries sell sections of hides, but also grade the whole hides with more attention paid to any irregularities in the most important areas or quadrants. Beyond the presence or absence of range marks or other flaws, and the hide section in which they appear (or don't), these various quadrants of the hide vary in consistency. If lesser hide sections are used (e.g., bellies), it will affect the quality and lifespan of the eventual bag made from them. Even full-grain is sliced from the back into fairly uniform thicknesses (measured in ounces), but some areas are just naturally stronger and with better surface texture than others, again as a function of biology. The different sections traditionally have different uses, but the "bend" or "butt" is generally seen as the best, a large continuous length that is the densest and most regular in consistency, graduating by degrees down to the "belly," which isn't good for much in a bag, often being too thin, weak, and even of a flappy, irregular density. You'll see occasional natural wrinkles and veins in the hides used in older Coach bags, but you'll never see weak spots and never bellies or anything like it (though you do in lesser bags of the period, hiding in side panels, gussets, interior pockets, etc.).

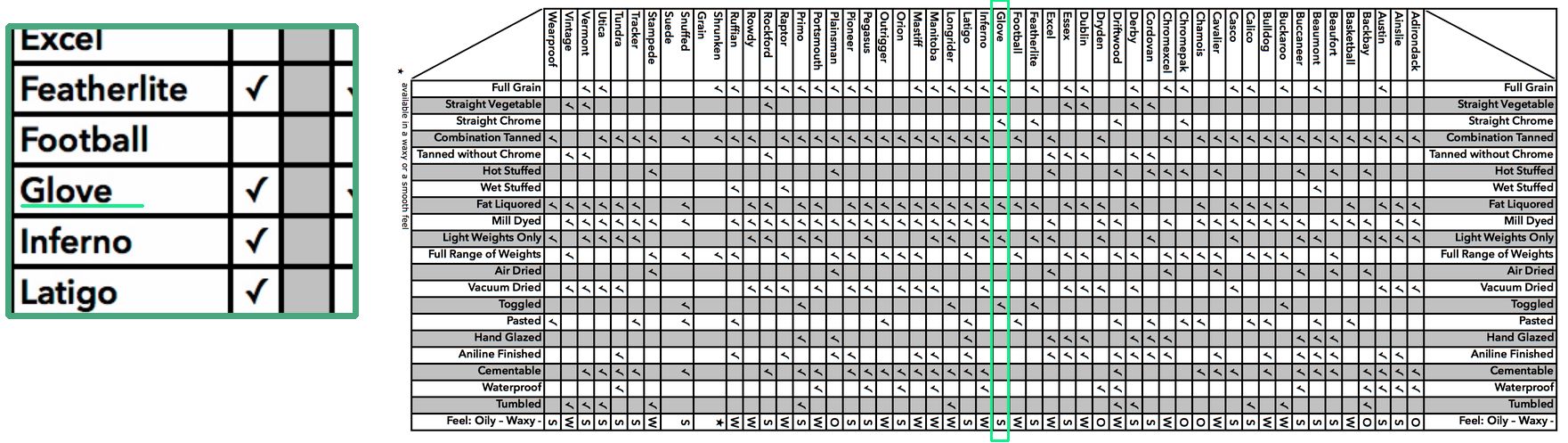

The way the four-tier model of leather grades makes it sound, a person could be forgiven for thinking that individual hides would be graded into one of those tiers, but it's not so. (The 4-grades thing is in use by a lot of outfits retailing men's leather goods today, but it's not in use by tanneries. It's the products made from those sections of hides, and how they're processed, that can be hierarchically ranked for quality.) Instead, many tanneries' finished offerings are grouped by intended end use (to make furniture, saddles, garments, footballs, etc.), or by a variety of names that describe a specific tannage (series of methods and processes), some in common use across tanneries (e.g., Latigo, Cordovan), and some devised and named by the individual tannery (e.g., "Java" at Tanneries Haas or "Chromexel" at Horween). Certain end-uses for leather require specific tannages, some traditionally employing full-grain hides, and some not. Just as a maker of handbags would develop a good reputation over time by adhering to a certain high standard of output, so it is with tanneries. Some tanneries' A grade full-grain hides are going to be superior to those of others, on the average. Some are better at certain tannages than others, too. We'll get into more detail on the particular tannage used for Coach bags in the section on "What is Glove-tanned?" below, but it's worth noting that one of the reasons those old Coach ads stressed that the leather they used was the same as in "Big League baseball mitts" was to point out the quality of the tanning. (You will sometimes hear a rumor that Miles Cahn only began using baseball glove leather for small leather goods because of some fluke where he got it on the cheap, but this is not to be credited. Baseball gloves had had about 60 years to develop into a specialty product by that time. Glove leather never went begging, least of all that tanned by the outfits supplying makers of mitts to the US major leagues.)

The naturally smooth surface of full-grain has always been valued and it's why tanneries generally select only the best or clearest hides from any given batch to make into full-grain tannages, since there are no additional processes (sanding, stamping, coating) to hide any irregularities in the surface. Every other kind of smooth leather is basically faux-grain because it's not the natural skin surface, the grain, but some artificial look-alike. It's the preservation of natural skin surface that counts, and only full-grain provides that truly durable and renewable surface, able to burnish and develop patina over time.

Coach bags were never really cheap, but it was because the materials themselves actually were superior, and turning those better full-grain hides into bags was highly skilled hand work. All the leather was a good quality full-grain, in every vintage Coach bag we've ever seen. They were noteworthy for it, and you actually could trust them. They also employed highly skilled craftspeople, and were proud of it (witness Miles Cahn's 1977 coffeetable book, The Factory, which was a sort of tribute to the workers at the NYC factory, showing members of Pocketbook Workers Union, Local 1, AFL-CIO on the shopfloor making belts and bags). On the first page of a catalogue from 1983 (below), we see such a craftsman positioning a die, with the bottom caption, "The cutter positions his dies carefully. He is mindful of the high cost of leather and is looking for choice cuts that will not throw off excessive waste." Why? Because the hides they were using were good full-grain, the best, the most expensive grade. Everyone knew it, and you could see it in the finished bags.

Thus, the use of full-grain leather --or not-- is fundamental, the single most significant factor in quality, both in terms of production cost and longevity. It's why the easiest metric of a good quality Coach bag is whether the word "full-grain" appears in the creed or not. The pricing wasn't trumped up or arbitrary back then, but followed a basic logic of costs of production and consequent benefits to the consumer. It was understood that a Coach bag would give many years of service, while developing a patina uniquely its own. Back then --because of the specific materials-- it actually would become your bag as it burnished, patinated, became unique.

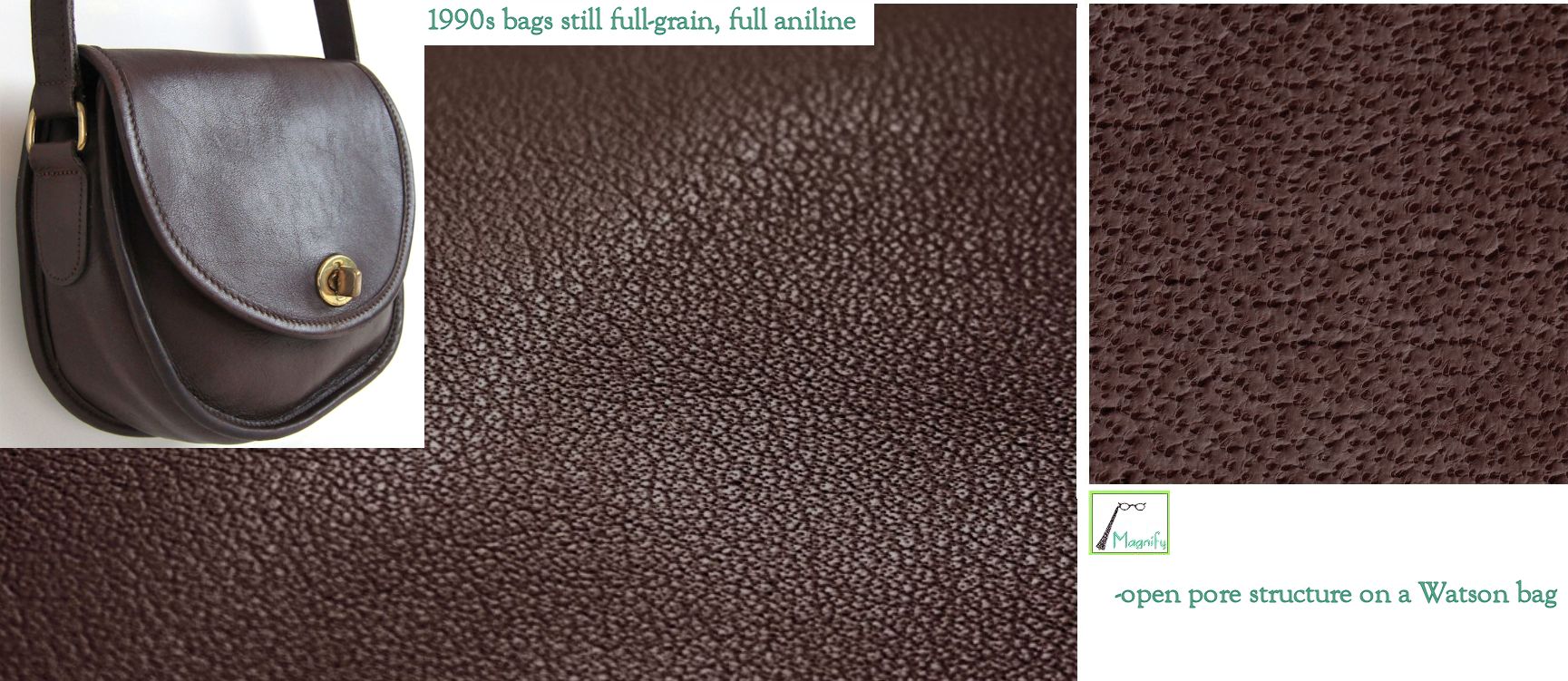

We'll get into the significance and process of aniline dyes further along, how to recognize full-aniline by the presence of pores (actually the easiest test of the true nature and quality of a leather bag), and some specifics of the "glove" tannage used in vintage Coach leather. But first, we have to get through those less-than-best grades of leather/leather processing, because everyone needs to know they're out there.

We consider all smooth-surfaced leathers not left as full-grain to be faux-grain...because their surfaces are manmade imitations of the natural grain markings found on animal hides tanned in their natural state. Before 1996, the US Federal Trade Commission, via its "Handbag Guides"/"Leather Guides," more or less concurred in this, i.e., that "leather" meant the old Top Grain, today called full-grain, but those days are gone. We'll get into the regulatory state of things that has allowed the near-total normalization of faux-grain leather shortly. But for now, we'll define faux-grain as leather made by imprinting fake grain-like markings, even simulated pore structures, on surfaces that were substrates of a hide, including coating those surfaces with paint and/or plastic. It can also mean imprinting or "embossing" the natural markings of one animal on the sanded down or split hide of another (e.g., ostrich quill pattern on cowhide). The vast bulk of garment and accessory leather on the market today is made of one variant or another of faux-grain, especially "top-grain/corrected-grain." This category stands in the middle between what we consider the good (full-grain) and the bad (genuine leather), and we'll just pretend we didn't really see the ugly (bonded leather). So we'll start with top-grain/corrected grain.

Below we have another diagram, an attempt at a sort of flow chart, from the splitting of the hides on the left to their eventual surfaces on the right. The first thing to take away from this is that today's usual meaning of top-grain is not at all the Top Grain of old, where it just meant the top half of the hide. Now it's "corrected grain," "laminated leather," "pigmented leather," because the surface you see is the natural markings of no animal. Although not as bad in terms of artificiality of surface and weakness of hide stratum as "genuine leather" usually is, today's top-grain is still a faux-grain because the hides used to make modern top-grain have problems, blemished surfaces that need to be "corrected" and are therefore not good enough to be used as full-grain (again, aniline dyes are translucent, they show the surface). So making top-grain involves use of lesser quality hides, sanding them down from the top --removing most of the grain including the natural surface-- and spackling with polymer pastes to fill up any remaining voids, sealing it with layers of opaque paint and synthetic coatings (usually polyurethane), and stamping ("embossing") a fake grain-looking pattern under high pressure and heat into what had been, until recently, a slightly fuzzy suede-like surface. It's supposed to look like a natural or intact full-grain...when it's not.

Corrected grain and top-grain are basically synonymous at this point, this new meaning of top-grain being completely normalized and forming the bulk of smooth leather used in 'better' handbags today. The processing of top-grain can vary to some degree by tannery, and some grades from each tannery are better than others in terms of less artificiality, but there is always a removal of the natural outer skin surface of the hide. (Easy way to remember how it differs from the older Top Grain halves model --in this top-grain the top is removed.) This is done with a goal of removing all irregularities in order to get a completely uniform, homogeneous surface. Everyone has seen this stuff because it's everywhere today. Total uniformity of surface is now taken as 'normal,' despite the fact that it's decidedly unnatural.

The mechanized finishing procedures used on corrected/top-grain are elaborate, and can vary to a degree. The typical sealing process is with liquefied paints and polymers, sprayed by rotating carousels of paint guns as the hides pass under on conveyor belts, then a stamping of faux grain patterns via mechanized rollers acting as dies. But there is overlap with some frankly more unpleasant methods seen in bicast, which involves more of a free-standing sheet of polyurethane/vinyl, and is usually conflated with "PU leather," a.k.a., "Genuine Leather," which has the layer of polyurethane/vinyl glued on top of split hides, rather than (heavily damaged, therefore heavily reduced) sanded-down grain-layer hides. It means there is variation in quality even within the category of top-grain/corrected grain, and some top-grain/corrected grain veers unappealingly close to bicast "PU leather"/"Genuine Leather," which is not legally considered leather at all in many places.

It may be easier to just watch a couple versions of these processes going down. Coach always used chrome-tanned leather (as does nearly everyone, vegetable and other tannages having become obscure these days). You can watch the chrome tanning and corrected/top-grain finishing process in a video from Fenice, above, about 13 minutes long (and sure to be 80s era footage, based on the music). We see some spackling of deep gouges ("stucco" @ 9:10) before the sanding off of the uppermost grain layer, then spray painting via paint guns in rotating carousels (10:00), artificial "embossed" grain patterns being stamped in by mechanized rollers (10:25), followed by dry milling or tumbling, and that batch of corrected/top-grain is mostly done. At about 11:00 we see bicast, a term now more common in automotive and upholstered furniture leather, but relevant as it began in the garment industry. If you watch this video through you'll understand just how bad "bi-cast" (i.e., bi, two, two layers) really is. The future surface of the 'leather' is the bright blue goop being poured out (11:25), built up by "creating the finishing film on a continuous support of release paper," which sheet is then glued and pressed onto either a split (suede texture) leather backing, like a decal, or onto a heavily sanded down piece of corrected/top-grain.

Thus, when the sanding of the grain surface is so deep, and the resulting suede-texture consequently so pronounced, that a mere sprayed pigment/sealant film won't cover it...things amounting to free-standing vinyl/pu coatings are then glued on. This overlap of production technique is rarely discussed, but shows that there are grades within top/corrected-grain, the lower end of which can be as bad as what gets marked "genuine leather," especially in the US. When that plastic surface is thicker than a film and more like a sheet of polyurethane on fabric backing, the only thing really distinguishing corrected/top-grain and "genuine leather" is the structure of the hide glued on the back (i.e., a sanded down part of the grain layer, vs a split layer from the corium). In those cases, any actual leather content does the consumer no good at all as leather, because it's the plastic you feel. This is really why we'd group corrected/top-grain with "genuine leather" in terms of being a faux-grain. It may be a thin film, or it may be a heavier plastic layer, but it won't breathe as real leather, it'll never burnish, and any leather in there is hidden from the user of the object anyway, so what's the point? It's no wonder most apparently-leather bags these days feel like rubber or plastic. We'd say it's because, from the point of view of the end user holding them, they pretty much are. And that shouldn't be.

Alternately, a longer video (above, about 25 minutes) from Optima, an Italian tannery, shows a slightly updated, environmentally cleaner process for making top-grain/corrected grain (skip the beginning without a strong stomach). Optima doesn't deal with splits/"genuine leather" at all, which you see traveling away early on to be sold to others. When the hides are shaved by the machine and the blobs go up the conveyor belts, that pulp is what is used in bonded leather. Later still, the sanding (as usual, euphemized as "buffing") produces a powder that was the natural grain, then on to "embossing" --fake grain patterns again, pressed in under high heat and pressure-- followed by huge rotating carousels spraying opaque paint/polymer mixtures. They're going for uniformity and homogeneity of surface, because uniformity has been normalized, and you can see them get it with a garishly shiny, plasticine bright red leather seen in flex-testing of the applied surface. Sure enough, it does all look the same in the end...but then so does a wood-grain decal on furniture. From our point of view, that finished red 'leather' shows the scope of the problem.

Thus, the new meaning of top-grain (= "corrected grain") is in large measure why a four-tier leather-quality model now exists, and nearly all modern handbags have that synthetic to semi-synthetic surface --except the vintage Coach bags. This homogeneous and 'blemish-free' surface may have its aesthetic uses (somewhere?), especially when 'the masses' have been conditioned to expect a 'perfect' uniformity in leather, but it does mean most modern leather has that slightly plasticine texture, which is why there has arisen such frequent public confusion in differentiating pleather (totally petro-chemical and synthetic) from leather (tanned hide of an animal). Because after processing, faux-grains aren't just uniform, but almost visually identical to and indistinguishable from PU. And is that really what we want in a leather bag?

So while top-grain/corrected grain wears badly compared to natural full-grain (the surface is artificial so it eventually wears through), it's still generally a better product than things being marked "Genuine Leather" today, first because at least some of the stronger grain layer is left, better tensile strength, and second because the bulk of it has only a comparatively thin film of paint and polyurethane on the surface, bonded in a strong way to the (part-grain) leather underneath. So while it is coated/laminated with some kind of film, at least it's usually not covered with a synthetic decal as seen glued to some (corium-layer) split hides. Because of the remains of that grain layer, it's structurally a bit stronger and better than "genuine leather" made from splits, the drop splits of old...what many, including many European tanneries, still consider rubbish.

A variety of terms are often heard with today's top-grain/corrected grain, some worth noting for their weasel-wordy qualities in use. Those old enough to remember Ricardo Montalban's "rich Corinthian leather," later admitted to be just a marketing term for a product coming out of a tannery in New Jersey, will have some background in this phenomenon.

"Corrected grain" feels decidedly euphemistic if you consider that "correcting" something generally means improving it. It doesn't ordinarily mean removing the desirable natural surface of something and substituting a fake one. "Laminated leather" is more accurate because after the natural surface is removed, lamination is what is done, with layers in varying thicknesses. (Coatings thicker than 0.15 mm run the risk of becoming "not leather" in much of the world, but US regulations don't even consider coatings as an issue, which we'll get to below.)

"Buffing" to describe sanding also really seems a stretch of language. "Snuffing" is also used, as in "snuffed top-grain," and it means sanding, but this term usually doesn't make it outside of tannery circles, and it's not being used in marketing patter. "Buffed" is. And any conventional understanding of buffing a surface does not mean abrading, planing or sanding it away, which we can easily see by the concept of buffing leather objects -- not with blades or sandpaper, but with a soft cloth. Instead, to buff is to polish something, usually with friction (heat) and pressure compacting some kind of fibers into a smoother, shinier state. Even burnishing (e.g., a "burnished edge" in leatherworking) is essentially polishing via compression and friction, having nothing to do with flawed-surface-removal. The mechanical procedures now used to produce "corrected/top-grain leather" involve removing the surface grain with abrasion and replacing it with something else, something made by machines, not nature. And the only thing that can really be "buffed" is full-grain leather, because it's the only thing with the intact natural grain surface fibers that could take a polish by being compacted. (You also can't "nourish" a sealed, fake PU grain layer, whatever anyone tells you about "nourishing" your bag with "leather milk"...but that's a separate rant.) You almost never hear anyone speak less than approvingly or at least apologetically about the modern meaning of top-grain, and the acceptance of "buffed" to describe a fairly violent or destructive process like being sanded down is one element of this. Corrected/top-grain is almost universally presented appealingly to the general public only because just about everyone is selling it now, and has a vested interest in making it sound good (and especially better than the competition, which is "Genuine Leather").

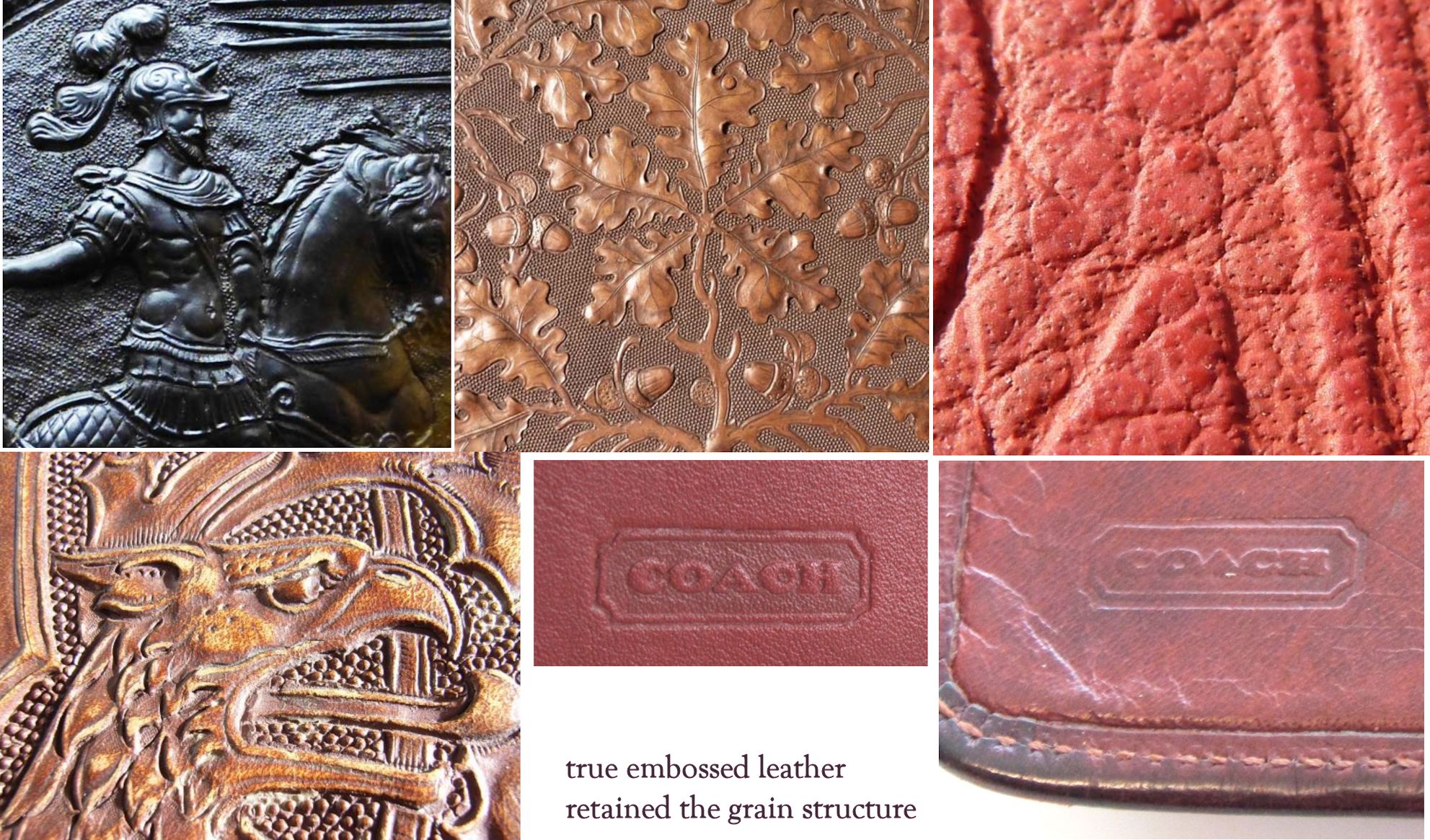

Today's so-called "embossed leather" is probably the most prevalent and disingenuous of the terms flying around in advertising patter, and the most worth noting. What it should be called, if anything, is "embossed-grain leather," because it bears no real relationship to the original or true meaning of embossing, which simply meant impressing patterns into the natural surface of full-grain leather for decorative effect, similar to tooling. The small incuse stamp seen in the earliest Coach marking (before the creed stamp there was just the word Coach inside a cartouche, stamped in a corner of the object), and even the old creed stamp itself, were technically a form of (actual, original) embossing. The full-grain surface was unaffected by this, just as the original meaning of "embossed leather" had nothing to do with removing layers of the surface, coating it with polymers, and stamping in something meant to simulate a grain. But that's what "embossing" is typically used to describe today, with "corrected grain," and that's hardly the same thing. (Leather quality standards are still alive in Germany; see the Leather-Dictionary description of full-grain with some more examples of these distinctions. That site also has some impressive examples of antique embossed leather from various parts of Europe, only a couple of which appear below, but it should be apparent, especially from the red piece at far left, that the natural grain, including natural pore structure, was always intact.)

We'd say there is quite a difference between real embossed leather, where the grain layer is left natural and overstamped with ornamental dies, verses the simulated grain-like patterns you see in nearly all modern leather handbags, pressed in by large mechanized rollers under which the sanded/split hides pass. Most of these are attempting to simulate a smooth natural cowhide-grain appearance, but they can be 'embossed' in any design imaginable. When the 'embossing' isn't a fake cowhide-grain design, it can be anything from faux alligator print and faux stingray to modern "crossgrain" or even a checker pattern, if you want it. Epi leather, caviar, saffiano, all of these are (sometimes proprietary) mechanically roller-stamped patterns, sealed with paint ("pigmented leather" = painted with opaque paints) and some kind of polymer coating. If there's a wrinkle in the hide or a skip in the machine (see below), the pattern ends abruptly. This roller-printed faux-grain = embossed idea is normalized now.

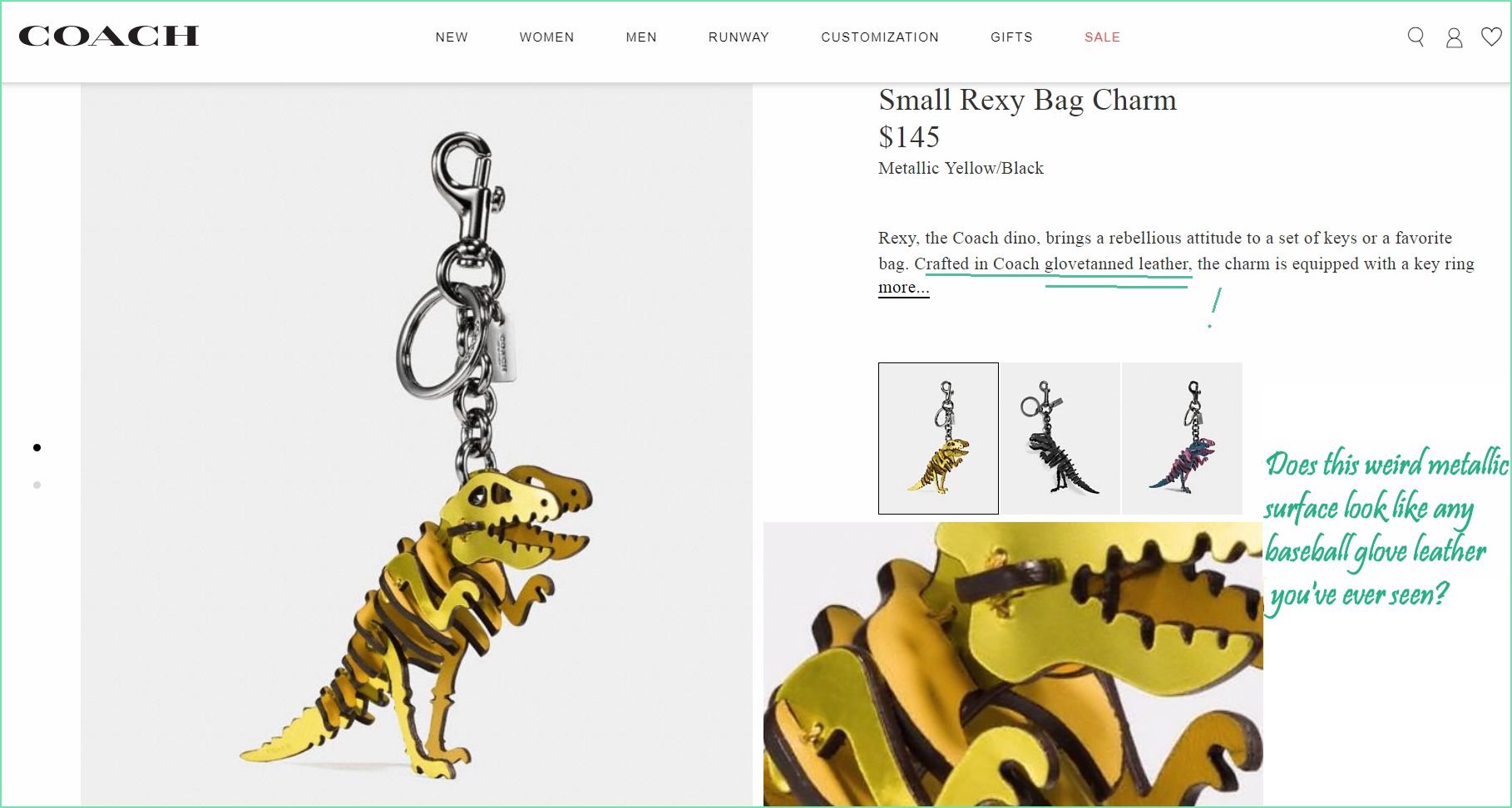

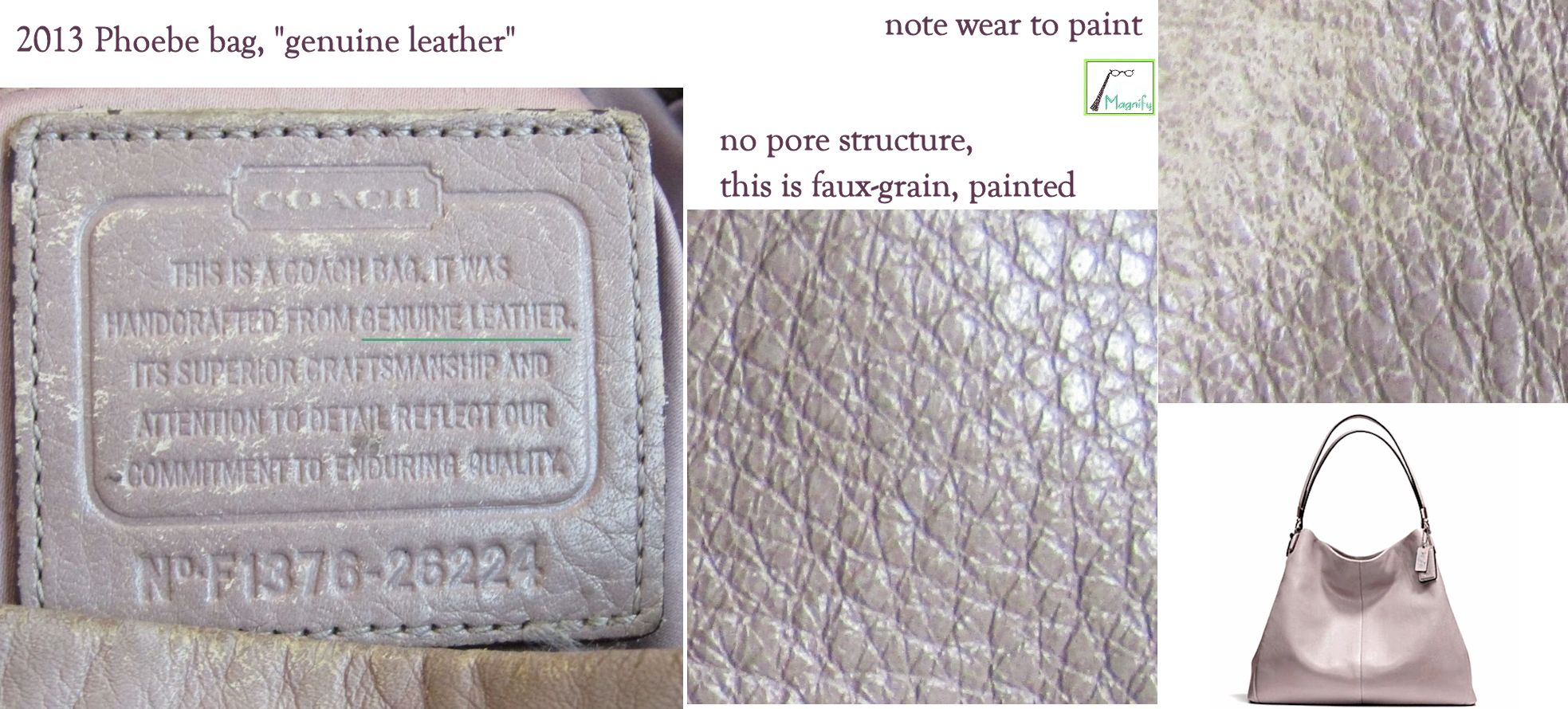

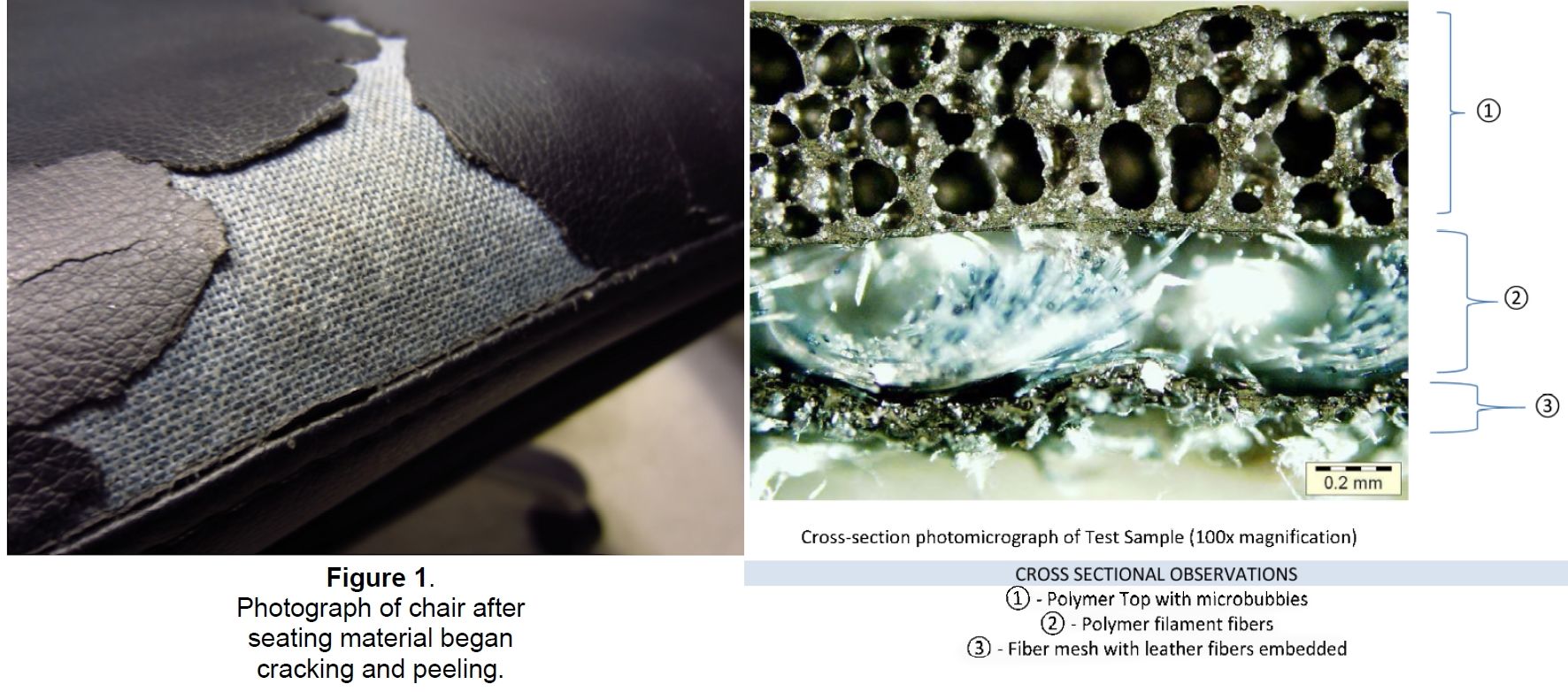

The big issue for all of us with a handbag --including a Coach bag-- is the feel of the surface in your hands, including over time. There was no plastic coating or paint on an old Coach bag, ever. Unusual textures changed nothing, it was always the hide's natural surface. This is not the same at all as what is being sold as "crossgrain," "sport leather," "polished pebble finish," "refined leather" or any number of other new marketing terms. (This situation has lately reached, we think, the final frontier of ridiculousness in the new "GENUINE GLOVETANNED PEBBLE LEATHER" marking seen on some recent bags. We'll be taking a look at some of the actual materials in some bags so marked, below, in section IV.)

The easiest way to understand why this matters is probably to look at some examples of traditional texturizing processes used on full-grain leather, compared to simulations of those surfaces in their mechanically stamped faux-grain versions. All of the texturing processes began as ways to enhance or draw up the natural grain on full-grain leathers, which is worth knowing, because you would never conclude this from modern ads, especially for "pebble finish" or "polished pebble leather." Coach used to stand out as the only major outfit still using all natural hides, leather that was not so processed, which is why mention was made in the creeds of any unusual techniques, including pebble grains like the Sonoma line. While the creeds explained some of the texturizing treatments, even without reading that, you could feel difference on the surface of a Coach bag. There was no frankenleather in Coach bags, ever, whatever texture the surface had. Until recently.

If you watched either of those tanning/finishing videos, it becomes apparent that any texture can be stamped into the sanded/split leather surface, along with making it any color by coating it with opaque paint (not dye), and any finish between matte and shiny. Usually the fake grain is just a simulated smooth full-grain cowhide pattern, but a stamped faux-pebble grain is gaining ground, including at the new Coach. Things described as "polished pebble leather" or "pebble finish," used today instead of "pebble grain," are 99% sure to be basically fake pebble grain. Why? Because true pebble grain requires the grain to be present and, on everything less than a full-grain hide, it's been removed. This is why the word grain has to be eliminated in advertising by most modern retailers. Because the product is not pebble grain, but one or another bumpy-textured faux-grain pattern stamped into sanded down or split hides by machines. (Ah, such luxury, huh?)

So what is a real pebble grain, then? A person could be forgiven for not immediately knowing today, so far has the industry as a whole slid into the normalized stamping of faux-grains. True pebble grain can only be achieved with surface-intact full-grain hides, simply because the texture derives from the inner fibers naturally present in the grain layer. Pebble grain is produced by drumming or tumbling the hides to soften them and create the irregular slightly-bumpy texture by raising the natural grain structure. This was usually done in an effort to increase the surface density, decreasing porosity by producing a constriction of the grain fibers themselves, and resulting in a toughened, denser, slightly lumpy surface as a form of waterproofing or scratch resistance. Each pebbled pattern was unique to each hide, based on its inner structure. It was never some repeating artificial linear design stamped in, as seen today in 'pebble finish.' And the only reason it was called pebble grain was a vague resemblance between the naturally occurring surface of tumbled full-grain cowhides that weren't plated (ironed, pressed) and small stones, pebbles.

An alternate (lesser-known) term for the same basic process is shrunken-grain, more common with sheepskin today but also done with cowhide, and producing the same result by accentuating the underlying grain structure through a constriction of the densest top later. (Those familiar with the older Dooney & Bourke "all-weather leather" bags with the duck emblem will recognize an iteration of this material; Dooney himself began by working under Miles Cahn at Coach in the late 70s.) True pebble grain leather is often a more expensive material to work with than regular (smooth surface) full-grain hides, in part because the hides shrink significantly during tumbling as the fibers draw together, and hides are priced by the square foot. Again, in a true pebble grain, there is no stamping or printing involved, ever. And it seems that should be stressed, as too many times we have seen people online authoritatively, and entirely idiotically, smacking down legitimate questions from bag owners asking why their newer 'pebble finish' leather bags rapidly show wear, when older pebble-grain ones didn't. This is why: full-grain tumbled, vs. faux-grain stamped and painted.

So real pebble-grain is a full-grain leather with the grain accentuated to add a degree of scratch-resistance and durability to it. "Pebble finish" or "pebble leather" on anything not full-grain is always a faux-grain, a cooked-up pattern pressed via roller-dies into a leather with the upper surface either sanded off (top-grain) or sliced away (split hides). This is easily illustrated with Coach bags, old and new, then and now. We can see a true pebble grain surface made from full-grain hides in any older Coach Sonoma leather bag. Some images below show that a description of the production process of actual pebble grain once featured in the creed on Sonomas, too. Again, the creed was a quality guarantee, which is why it bothered to state these production details.

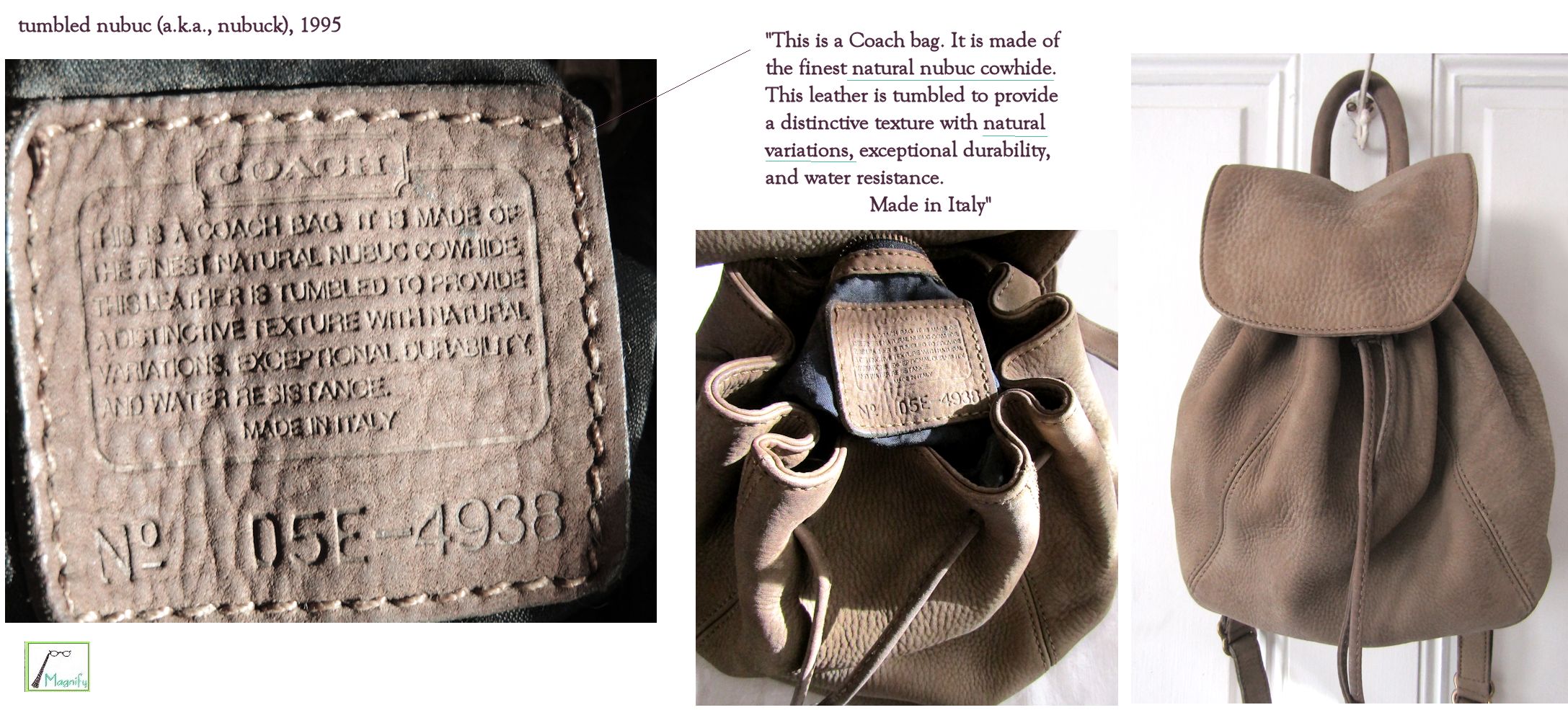

The same also applies to a tumbled (pebbled) nubuck from the mid-1990s (nubuc = nubuck, and nubuck means a full-grain). Nubuck itself, even though very lightly sanded or snuffed to achieve a velvety nap, is still always a full-grain, the whole grain surface intact, and not at all comparable to top-grain/corrected grain. In nubuck, the surface is roughened a bit, but on the order of microns, not millimeters, and the creation of that very fine velvety nap could never conceal pre-existing flaws in the hide. Corrected/top-grain differs, first, because the hides used are by definition flawed, far too damaged ever to be used as full-grain/nubuck, and those flaws are being hidden by removing an entire upper layer of the surface. Second, because corrected/top-grain isn't left in that open, raw state (a suede), but is instead plated (ironed) and stamped ("embossed") with an artificial grain-like pattern, coated with sprayed paints/polymers, the result is an artificially smooth surface that imitates smooth leather. Like true pebble grain, nubuck and pebbled/shrunken nubuck are specialty variants of full-grain leather.

Finally, "milled" was another word sometimes used in old Coach creeds, but it generally described a process of tumbling or boarding, which is a finishing treatment that stretches the natural fibers under tension and pulls the underlying grain patterns to the surface, creating a texture of crosshatching or parallel wrinkles, also unique to each hide. These wrinkles are natural to each surface, and a far cry from homogeneously stamped linear patterns produced by metal rollers or dies, as in 99% of the modern versions of textured leather.

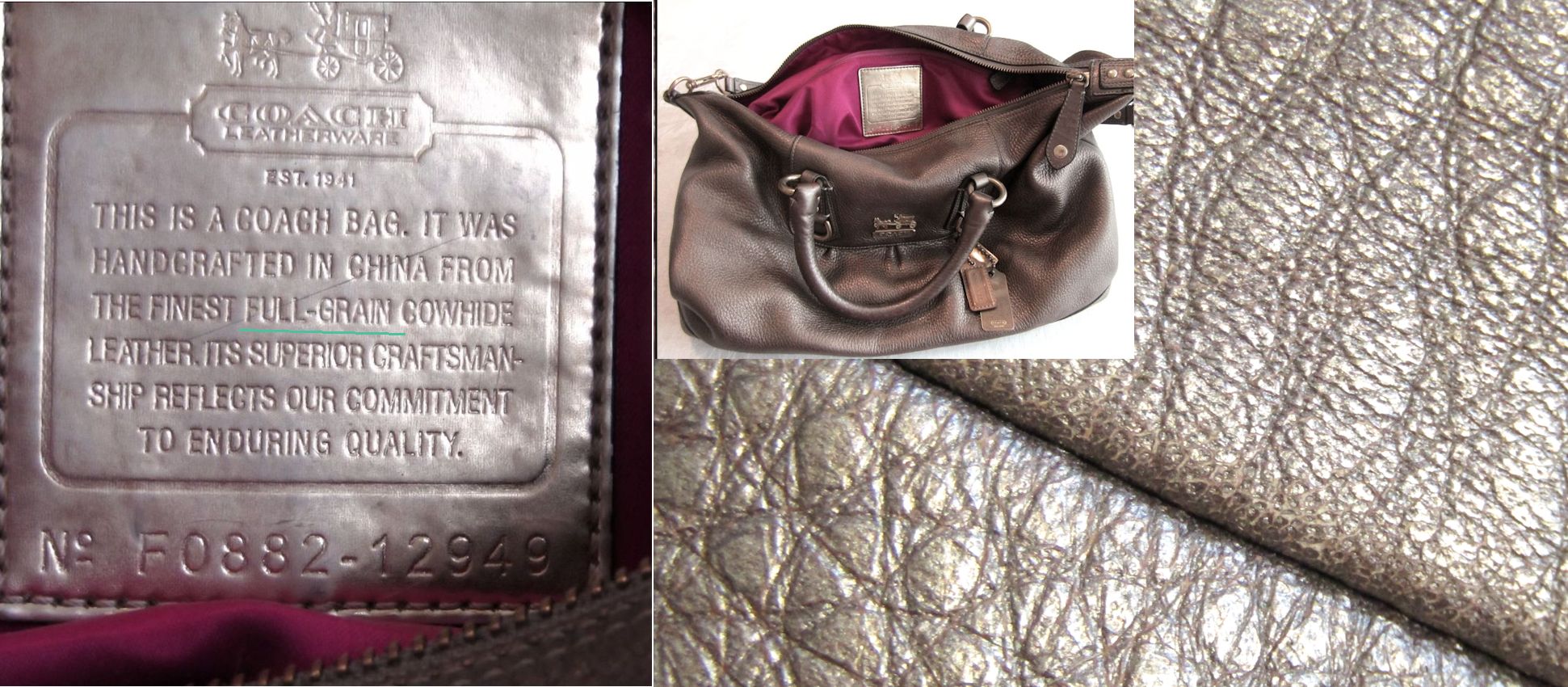

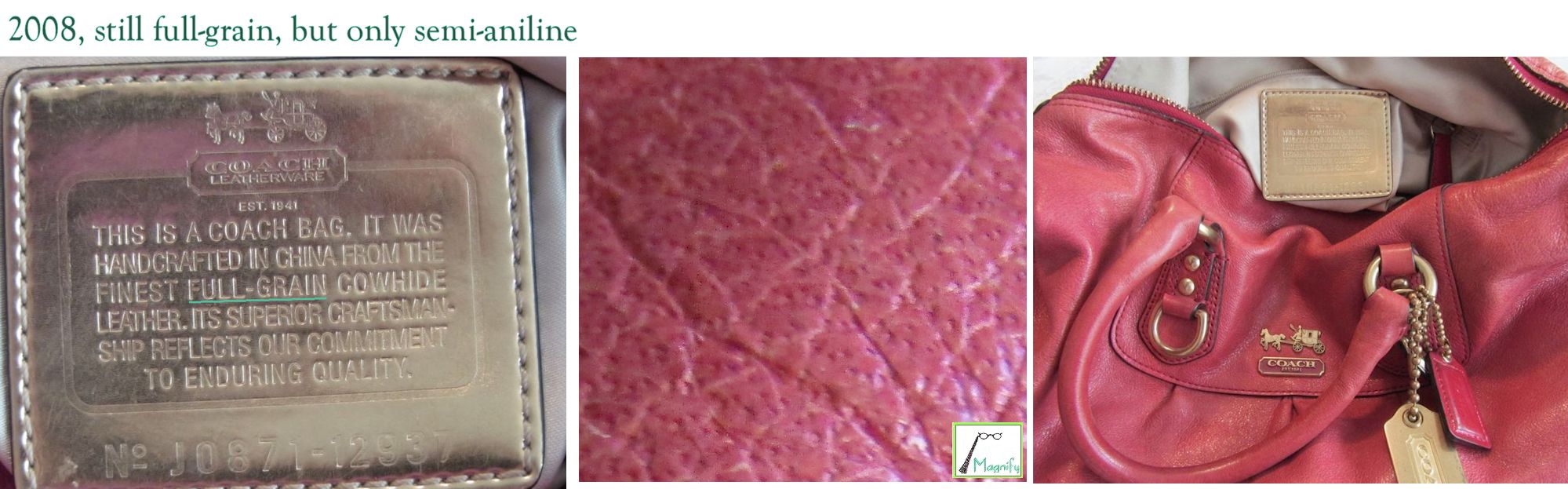

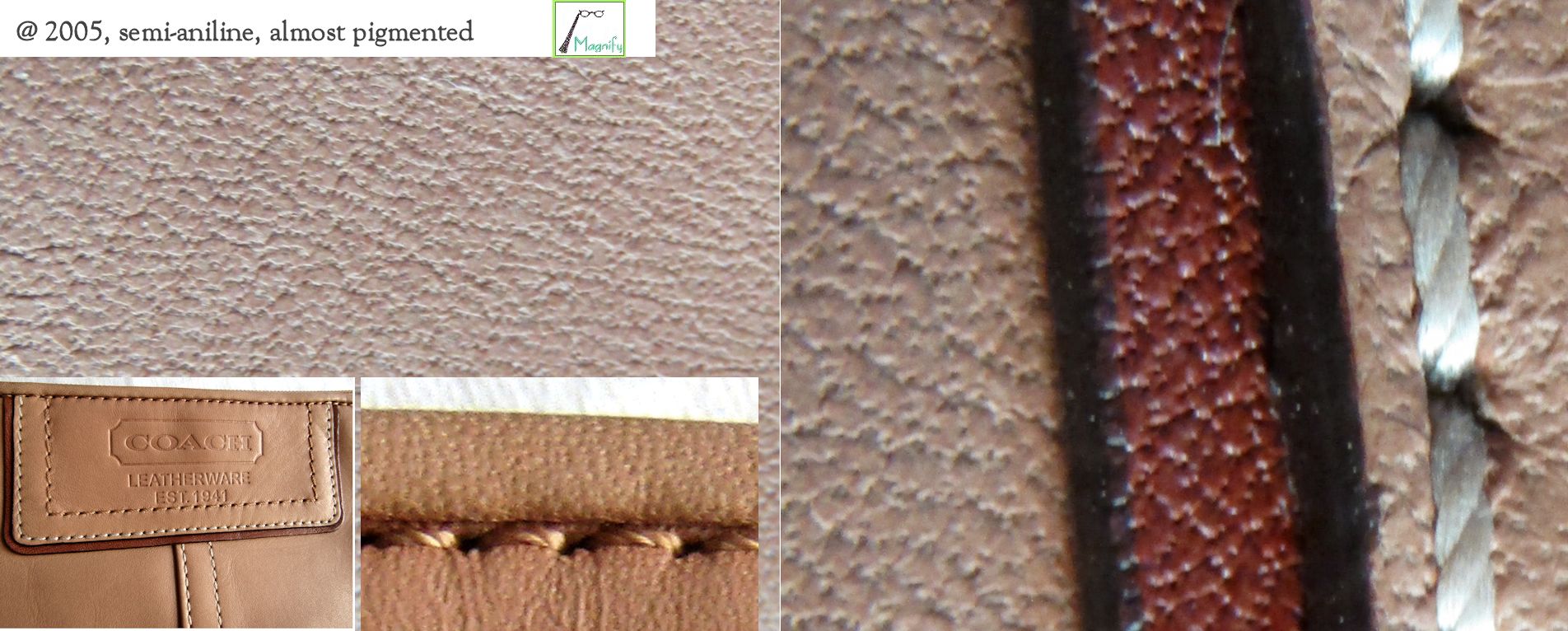

It's worth noting that Coach continued to produce bags in this older, natural (pebbled/shrunken/boarded) way even well after 2001, until about 2010, in the usual range of colors, but even in metallics, as seen below. The creeds of those later bags, though made in China, show us that full-grain leather was still standard with Coach at that point, with the textures produced from the natural grain, even when foiled, which surprises many people. (Metallic or foiled leather is a separate treatment, distinguishable here from faux-grains by the fact that the foil is microscopically thin, and laid upon a natural full-grain hide, still with visible pores. It's somewhere on a par with semi-aniline leather, dyed but with trace-pigmented surface, which we'll look at soon. Metallic full-grain leather is always more fragile as a surface in terms of scuffs, as the foil is extremely thin, but it's no less strong than non-foiled full-grain as a material in terms of tensile strength. And it's certainly qualitatively far better than what is being called "Genuine Leather" today.) Below, a Bonnie satchel in metallic gold from 2008 and a Sabrina bag in bronze metallic, from the same year. Both are still full-grain.

Thus, we feel there is a world of difference between full-grain bags with textured designs drawn out by raising of that natural grain, verses 'embossed' faux-grain: things with simulated patterns stamped into a manmade (grain-less) surface, then sealed with paint and polyurethane.

Making out that this is any kind of product of nature seems sort of galling if looked at this way. And worse still if there is a suggestion that it is unique --which each real pebble-grain surface is-- or will improve with age, rather than just wear though to a substrate of usually greyish suede. But new-Coach doesn't have to worry about that, what with the new single year warranty. Slap some "beloved" cartoons on it and everyone will be happy enough with their printed faux-grain "polished pebble leather" plastic-coated Disney bunny bag. Won't they?

Well, obviously some of us will never see the word "elegant" in the same line with "Thumper" and not retch just a little bit. Others can never hear things like this called "iconic" without a giggle. So there has to be an option outside of these faux-grains and cartoons. We think the best one is to get to the bottom of exactly what it was about the saturated, naturally dimensional surfaces on those old Coach bags, in order to understand it enough to demand the return of it at Coach or, failing that, seek it out elsewhere if it does come to that. And the thing that made the now-vintage Coach handbags stand out, even more than the exclusive use of good full-grain hides, was the use of pure aniline dyes. There is a very depressing lack of full-aniline bags of all kinds on the market today in the US, perhaps because not enough of us know what that means anymore, and therefore don't yet know enough to demand them back. But this can remedied.

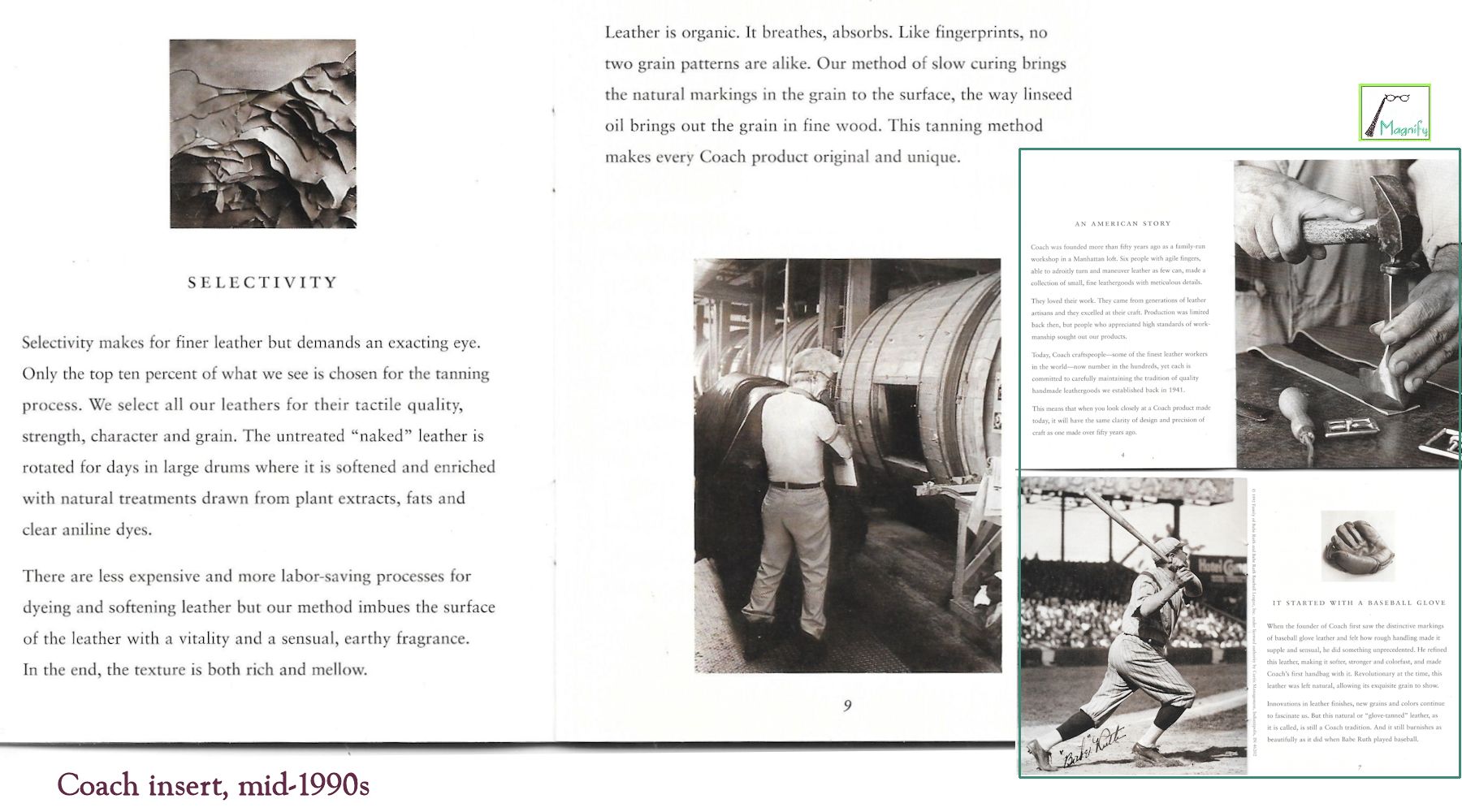

There is indeed more to that satiny, pleasantly natural surface of vintage Coach leather than just the part of the hide from which it came. There's the method of coloring, which came from immersion in a liquid dye bath rather than paint sprayed over and obscuring the surface. Precisely because Coach leather was always full-grain --and only clear full-grain hides are left natural to show their unique grain markings-- Coach bags could be colored with anilines. Aniline leather is more expensive to produce because it's a time-consuming step, a dye bath rather than a quick trip under the carousels of spraypaint guns, and only the best hides are clear enough to be left full aniline, nothing hidden. Even as late as the mid-1990s, Coach marketing (see "Selectivity" below) still mentioned the benefits of aniline dyes, still comparing it to linseed oil or translucent stains on good wood, enhancing the appearance of the natural grain, rather than coating and obscuring it as with opaque paint. (Note, as with the "sic" in the 1975 Courier bag ad, technically "cured" is inaccurate, has nothing to do with tanning/retanning or dyeing, but is actually a step that happens before hides enter the beamhouse. Curing is salting, for preservation, but this is a minor terminological point, and Coach generally got things right in the wording of their ad copy. For a run down on the most common tannery terms, see a good Glossary from the International School of Tanning Technology.)

The aniline dyes are a very significant aspect of the old Coach bags, and had a real bearing on their appearance, texture, and especially longevity. Aniline was actually the first synthetic dyestuff, though it is still technically organic, a material derived from coal-tar discovered in the mid-19th century in an unrelated attempt to cure malaria with quinine. First as mauveine, then fuchsine, anilines rapidly overtook unpredictable and expensive vegetal/mineral dyestuffs in coloring wool carpets, all sorts of Victorian textiles, and eventually leather. It was good for leather in particular because aniline is soluble with oils and oils are crucial to a number of tanning processes (fat liquoring), making for supple leather. Consequently, vat dyeing with aniline/oils produces a superior leather (this is what that ad was trying to describe as 'cured with'), because it saturates through the hide, from suede side to surface, rather than merely forming a surface coating.

This is quite different from "pigmented leather," where pigments mean solid, opaque color particles resting on a surface, rather than color truly in solution as a liquid, as with aniline, permeating the hide from front to back. Pigments are paint, forming an opaque film on just the surface, as we saw in the typical 'corrected-grain/genuine leather' products. Because the paint is only a film on the surface, obviously the color wears away or may even peel over time, which irreparable problem doesn't afflict aniline dyed leather -- as so many decades-old Coach bags around today show. The nature of the coloring method, and its permeation through the entire hide, is why those old Coach bags can usually be easily refreshed if scuffed, while the modern 'faux-grain' painted/pigmented leathers really can't, unless carefully color-matching and re-painting them, usually with some kind of acrylic. (And really...just yuk.)

Because full-grain leather is the outer skin surface, with just the hair removed, and full aniline means no treatments beyond the dye, aniline leathers are porous and the natural pore structure of the hide remains intact and open. This makes aniline dyes a key element in both the quality and longevity of vintage Coach bags, but also provides us a useful method for identifying older Coach products and distinguishing them from lesser bags made by others. This natural pore structure, open and free of clogging paints, is usually visible under strong magnification, as with a 10x jewelers loupe, and a few minutes with a $3 loupe will often tell you something far more useful than hours of looking at zipper brands or scrolling 'lists of fake serial numbers' or any of the other numerical minutiae one often hears about online in the great "flood of fakes" panic regarding Coach bags. We'll have more to say about this, and the concept of "authenticity" in general, below. For now we'll just say that more and better answers are often found by going down to the level of concrete materials. There is a paucity of discussion on concrete materials, both why they matter and how to identify them, which is one of the information gaps this screed hopes to partially remedy below (IV. Concrete Materials Analysis), when we take a loupe to the leather and look at pore structure in Coach bags from several periods.

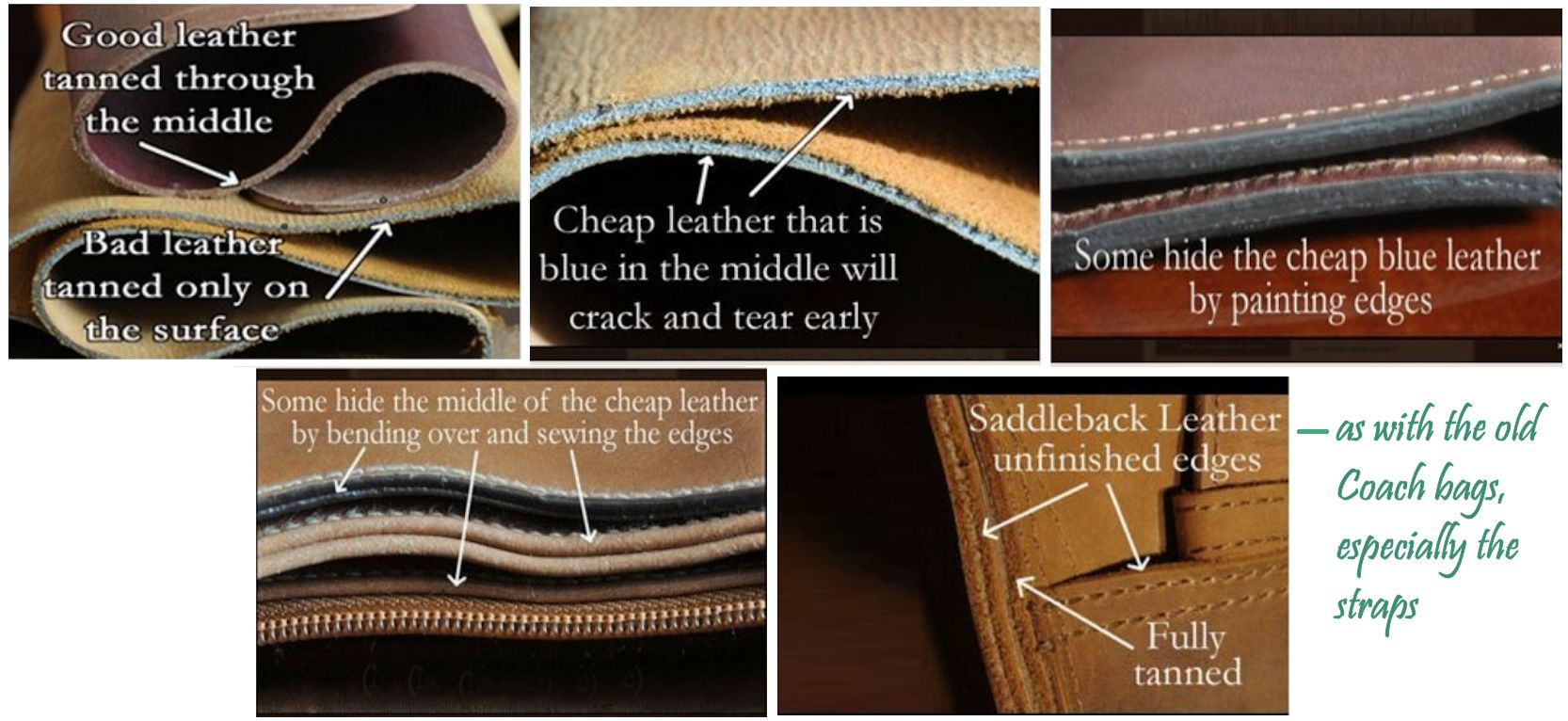

Beyond the open pore structures on the uncoated exterior surfaces, another place you can see the use of anilines in many old Coach bags is the suede interior (most 1970s-1990s bags weren't lined with fabric) and the edges of the straps, which weren't coated as on the modern bags, but instead left natural and showed a cross-section of the whole hide. Because aniline dyes penetrate the whole hide with color, suffusing it from front to back, it can't wear away like a surface treatment, peeling at the edges, and thus the straps could be left without plasticized binders or trim, as on current bags. That visible cross-section of the hide is actually another marker of leather quality, as it tells us that the tanning was thorough, with no corners cut, and that the color was thoroughly dyed -- not a thin surface coating of paint.

When unusual efforts are made to conceal the cross-section of the hide, say on the straps, it generally bodes no good, and may even be hiding leather that is incompletely tanned and left in a partial wet-blue state (chrome tanning produces a characteristic blue color at one stage of the process). The images above come from Saddleback Leather (which uses good full-grain hides, but only makes basic men's bags), from a nice page explaining some of the sleazy methods in use by bad tanneries to conceal insufficient tanning. Many of the same edging methods are used with non-aniline or surface-coated-only leathers, not in a deliberate effort to conceal bad tanning, but because surface-treated faux-grain leathers need that edging to slow down the chipping and peeling to which those surfaces are prone because the color is only a thin surface layer.

This means we lose information about the leather quality when makers add fabric linings, sew edges under, and/or coat the edges with paint/plastic. (Coated edges are not the same thing as burnished edges. This edge issue will become more relevant when we move on to the new versions of Coach purse straps, and specifically how they wear, compared to the old, exposed-suede-edge straps.) On a vintage Coach bag, you could usually see a cross-section of the hide on the edge of the strap, which was left natural, not as a shortcut, but as an indicator of quality. The sturdiest bags will typically have a piece of polyester rope, cord, or fabric tape sewn inside the two halves of the strap, primarily because leather will eventually stretch out under tension and weight without it. (You can actually watch a tubular strap being made by hand here, roughly of the type used on the old shopping tote, including the insertion of a length of polypropylene rope for strength.) Sometimes you can just make out the edge of this fabric tape layer on flat two-part Coach handles, usually under magnification of the cross-section or, on the rare occasions when a tubular handle eventually does wear through the leather layer from decades of use, you can see the rope layer inside. (It's worth knowing that this is what that inner usually-whitish layer is, nothing shady, but actually a sign of quality, a binding layer there for reinforcement against leather-stretch.)

Outside of the leather furniture industry, you don't hear much about aniline dyes today, but it's actually that unsealed aniline dyed surface that is the essence of why one thing feels and wears like good leather, natural and breathable, while another thing feels slick and plastic-coated, briefly, then rapidly looks worn as soon as that surface coating is scuffed or handled. Full-grain hides dyed in aniline are a world apart from all lower-tier split hides stamped with a fake grain, painted and sealed with plastic. Sadly, that later material is what is usually labeled "genuine leather" these days, and much of it may as well be pleather, for the way it feels, wears, and wears out. The structural difference is akin to a tenderloin, verses chuck beef, while the external difference is comparable to oiled mahogany verses particle board with a 'woodgrain' decal. It's a serious difference in materials quality and it has consequences for both how a bag feels in your hand, and how long you can use that bag.

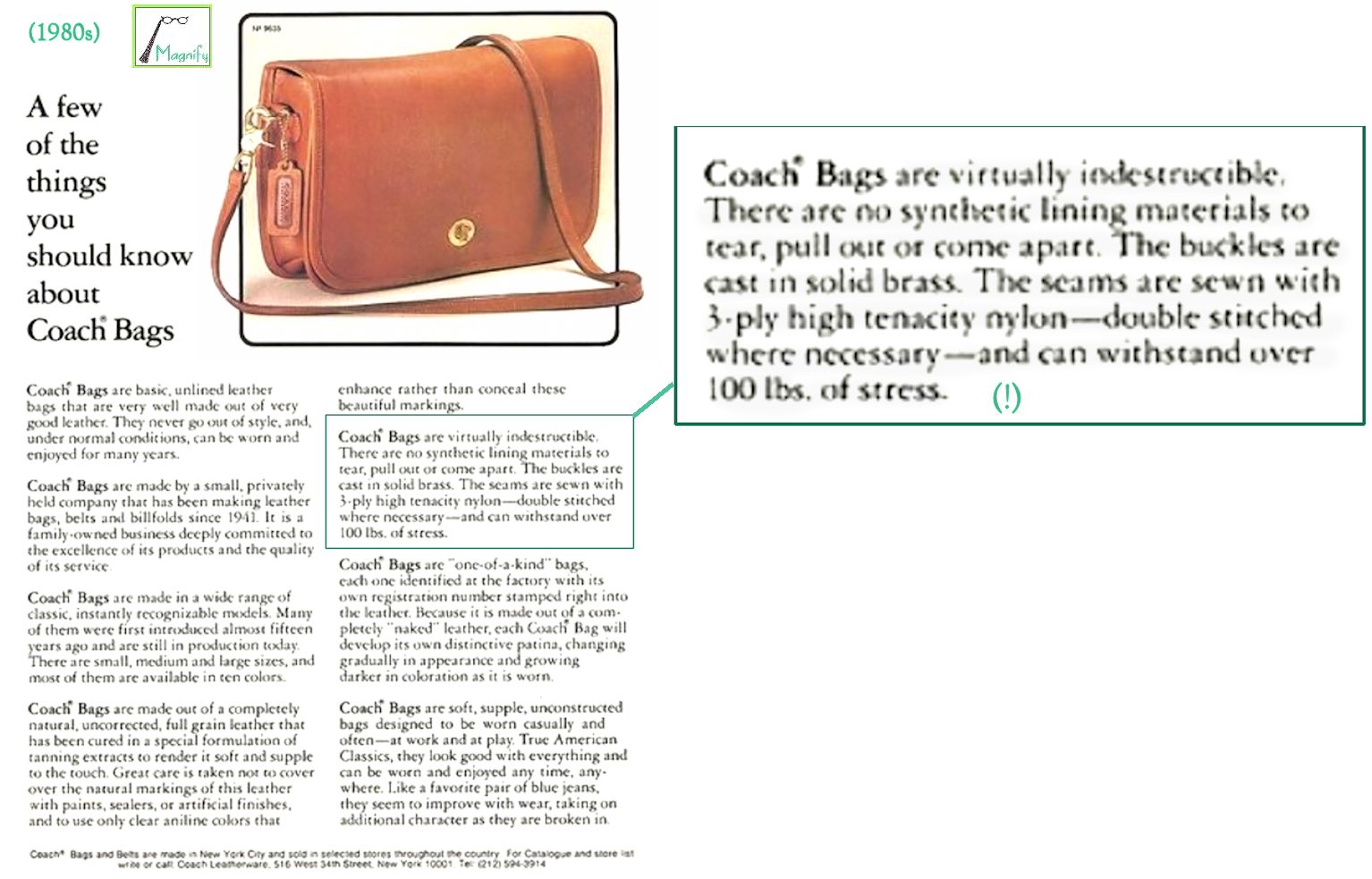

To sum up, the use of good grades of full-grain, full-aniline leather is why the older Coach bags can remain in use for literally decades and, with minimal cleaning and conditioning by the owner, stay looking good. The thickness of the leather (weight in ounces) may vary, but a full-grain hide, unsealed with plastics or paints, but instead through-dyed with aniline colors, is indefinitely renewable in a way leather with mere surface coatings simply never is and never can be. Together with the solid brass hardware that was once standard on older Coach bags, this type of leather was the real reason Coach could offer a lifetime warranty, where you could send your bag back to the NYC factory for free refurbishment even multiple times, and it would come back still looking like your bag, but refreshed and happy, ready for more years of toting. It was specifically meant to be renewable in all components. The hardware also wasn't plated pot metal or zinc back then, but solid brass, specifically so that the surface never wore off. Even back in the 70s, most handbags used nickel plated zinc hardware, which was objectively inferior to Coach solid clips, d-rings, and turnlocks. As the 80s catalogue page below shows, the words "virtually indestructible" actually appeared in ad copy. Even the 3-ply nylon thread and a weight-bearing capacity of 100 lbs. was mentioned!

There were several essential quality materials used in the old Coach bags --full-grain, full aniline, solid brass-- and taking away any one of them changes not just the look or the feel, but the lifespan of the bags, too. The long lifespan and ability to change and improve with use was always a central element to the Cahn's product concept. And now we know enough about those basic materials to understand the idea of "glove-tanned."

So old Coach bags were made from full-grain leather --the hide's natural surface-- vat-dyed with oil-based aniline dyes? Yes. And then the leather was glove-tanned in a special secret technical process known only to and used only by Coach? No. Some of the later Coach promotional material does kind of make it sound that way, as do many of the current silly puff pieces you encounter constantly on the web. But the truth is quite different. Understanding exactly what "glove-tanned" means just became more crucial, too, since more recent Coach/Tapestry marketing has elected to stretch (we feel, maybe even pollute) this branding concept as "GENUINE GLOVETANNED LEATHER," all run together as one word, and now printed on the bottoms or backs of certain reissued/'archival' bags (see ex. below) that are now being made of mere 'genuine leather.' Some of us have even begun to suspect that this move indicates a hope that young buyers may become (even more) confused, mistaking "glovetanned" for some known benchmark of leather quality, and thus failing to notice the switch from good full-grain leather to the lower-quality splits found in 'genuine leather.' For the record, full-grain actually is a benchmark of leather quality. "Glove-tanned" is not, and was always a branding concept. This recent use of the new GLOVETANNED makes a look at the origins and meaning of glove leather worthwhile.

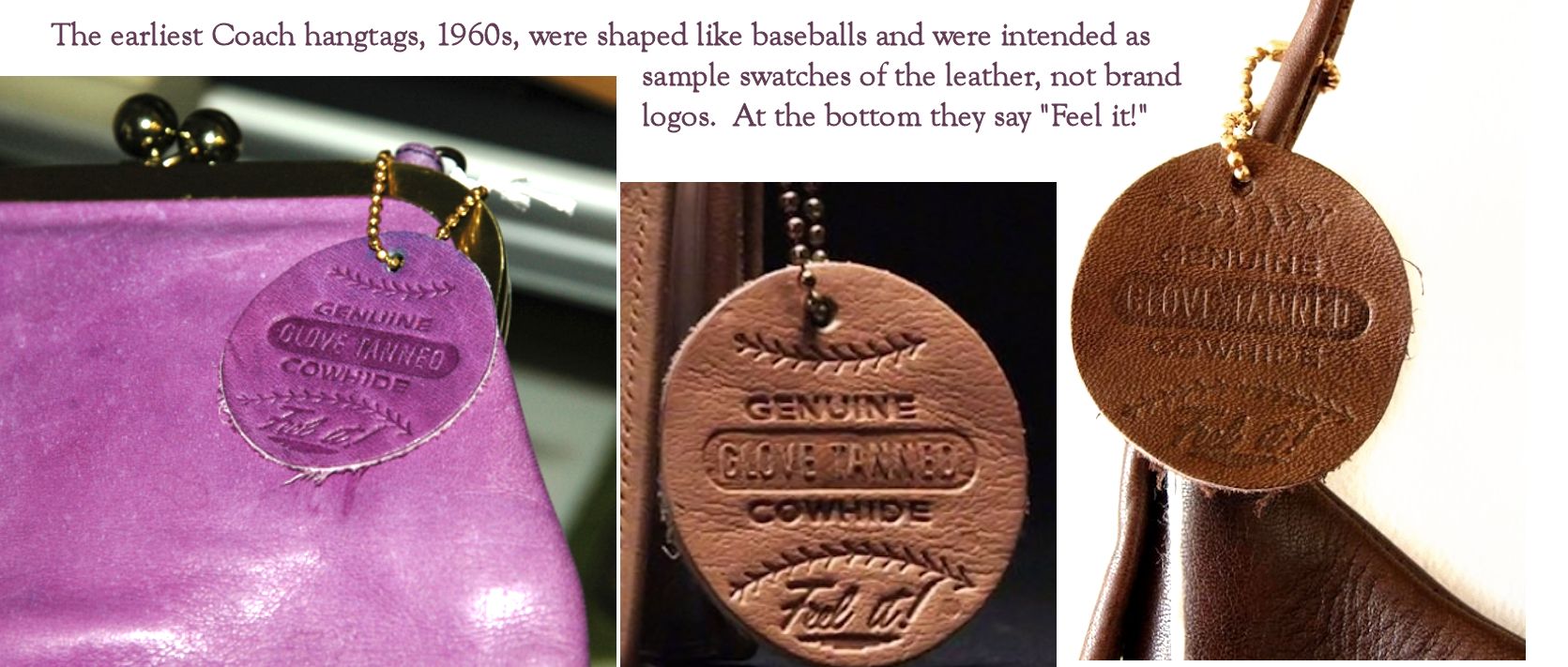

As we saw above in the early 1960s ad for men's travel cases (glove-tanned "available for the first time"), Coach began using the glove-tanned term only in the early 60s, first for men's small leather goods, which was their product line to that point. (Things a person may encounter on-line about Coach making glove-tanned leather handbags since 1941 are simply wrong. So much on the internet is simply wrong.) In their usual low-key way, they described how this particular tannage had benefits in longevity and durability. There was no question about the nature of it, as the ads made amply clear, because the baseball mitt origin was seen as a selling point. We can also see this very directly from the surviving examples of the earliest Coach hangtags used on bags. These were circular, with graphics clearly suggesting the stitching of a baseball, and bearing the words "Feel it!" imprinted on them. In other words, it's baseball glove leather, feel it for yourself. The idea of the hangtag itself was originally intended, not as some 'designer label,' but as a sample swatch, meant to show the texture and quality of the glove leather from which the bag was made. (This function as a swatch is also why so few of those tags survive today, because they were meant to be disposable, something to show buyers the source and type of leather, and allow them to rub a little piece of it between the fingers. Once you bought the bag, the swatch/tag had served its purpose and was generally removed, as paper retail tags are today.) The original Coach company was always focused on the quality of the leather used in their bags, including with a bag made of Glove leather.